What is Convection

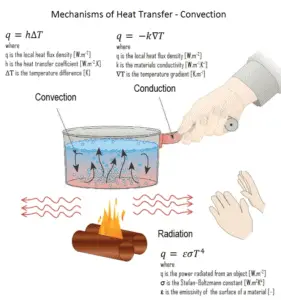

In general, convection is either the mass transfer or the heat transfer due to bulk movement of molecules within fluids such as gases and liquids. Although liquids and gases are generally not very good conductors of heat, they can transfer heat quite rapidly by convection.

In general, convection is either the mass transfer or the heat transfer due to bulk movement of molecules within fluids such as gases and liquids. Although liquids and gases are generally not very good conductors of heat, they can transfer heat quite rapidly by convection.

Convection takes place through advection, diffusion or both. Convection cannot take place in most solids because neither significant diffusion of matter nor bulk current flows can take place. Diffusion of heat takes place in rigid solids, but that is called thermal conduction.

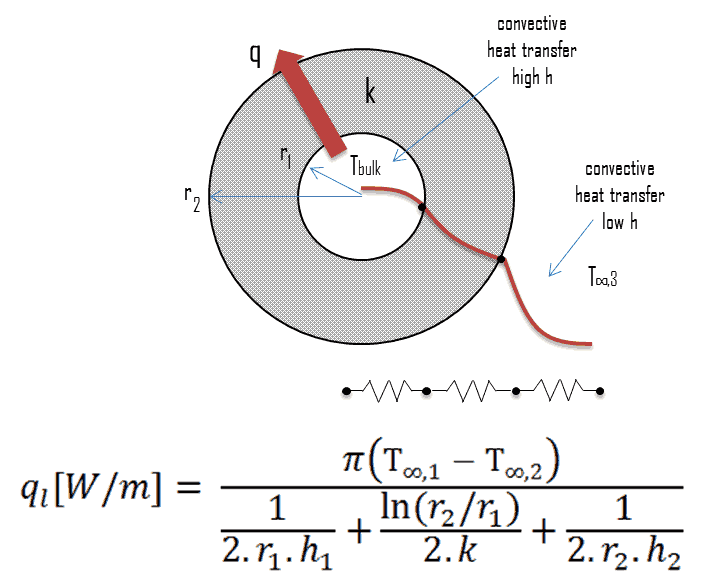

The process of heat transfer between a surface and a fluid flowing in contact with it is called convective heat transfer. In engineering, convective heat transfer is one of the major mechanisms of heat transfer. When heat is to be transferred from one fluid to another through a barrier, convection is involved on both sides of the barrier. In most cases the main resistance to heat flow is by convection. Convective heat transfer take place both by thermal diffusion (the random motion of fluid molecules) and by advection, in which matter or heat is transported by the larger-scale motion of currents in the fluid.

Mechanism on Convection

In thermal conduction, energy is transferred as heat either due to the migration of free electrons or lattice vibrational waves (phonons). There is no movement of mass in the direction of energy flow. Heat transfer by conduction is dependent upon the driving “force” of temperature difference. Conduction and convection are similar in that both mechanisms require the presence of a material medium (in comparison to thermal radiation). On the other hand they are different in that convection requires the presence of fluid motion.

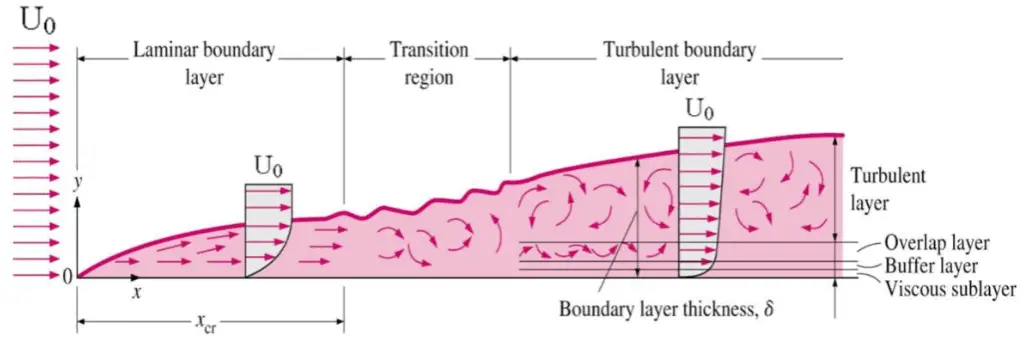

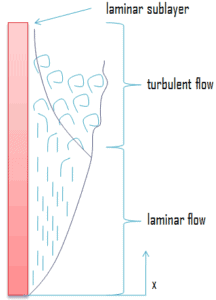

It must be emphasized, at the surface, energy flow occurs purely by conduction, even in conduction. It is due to the fact, there is always a thin stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface. But in the next layers both conduction and diffusion-mass movement in the molecular level or macroscopic level occurs. Due to the mass movement the rate of energy transfer is higher. Higher the rate of mass movement, thinner the stagnant fluid film layer will be and higher will be the heat flow rate.

It must be noted, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer and therefore nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to bulk fluid.

As was written, heat transfer through a fluid is by convection in the presence of mass movement and by conduction in the absence of it. Therefore, thermal conduction in a fluid can be viewed as the limiting case of convection, corresponding to the case of quiescent fluid.

Convection as a Conduction with Fluid Motion

Some experts do not consider convection to be a fundamental mechanism of heat transfer since it is essentially heat conduction in the presence of fluid motion. They consider it to be a special case of thermal conduction, known as “conduction with fluid motion”. On the other hand, it is practical to recognize convection as a separate heat transfer mechanism despite the valid arguments to the contrary.

Heat transfer by convection is more difficult to analyze than heat transfer by conduction because no single property of the heat transfer medium, such as thermal conductivity, can be defined to describe the mechanism. Convective heat transfer is complicated by the fact that it involves fluid motion as well as heat conduction. Heat transfer by convection varies from situation to situation (upon the fluid flow conditions), and it is frequently coupled with the mode of fluid flow. In forced convection, the rate of heat transfer through a fluid is much higher by convection than it is by conduction.

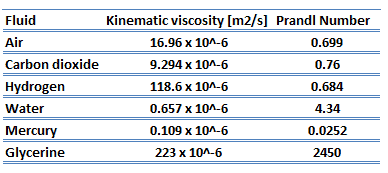

Heat transfer by convection is more difficult to analyze than heat transfer by conduction because no single property of the heat transfer medium, such as thermal conductivity, can be defined to describe the mechanism. Convective heat transfer is complicated by the fact that it involves fluid motion as well as heat conduction. Heat transfer by convection varies from situation to situation (upon the fluid flow conditions), and it is frequently coupled with the mode of fluid flow. In forced convection, the rate of heat transfer through a fluid is much higher by convection than it is by conduction.In practice, analysis of heat transfer by convection is treated empirically (by direct experimental observation). Most of problems can be solved using so called characteristic numbers (e.g. Nusselt number). Characteristic numbers are dimensionless numbers used to describe a character of heat transfer and can be used to compare a real situation (e.g. heat transfer in a pipe) with a small-scale model. Experience shows that convection heat transfer strongly depends on the fluid properties dynamic viscosity, thermal conductivity, density, and specific heat, as well as the fluid velocity. It also depends on the geometry and the roughness of the solid surface, in addition to the type of fluid flow. All these conditions affect especially the stagnant film thickness.

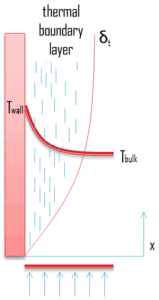

Convection involves the transfer of heat between a surface at a given temperature (Twall) and fluid at a bulk temperature (Tb). The exact definition of the bulk temperature (Tb) varies depending on the details of the situation.

- For flow adjacent to a hot or cold surface, Tb is the temperature of the fluid “far” from the surface.

- For boiling or condensation, Tb is the saturation temperature of the fluid.

- For flow in a pipe, Tb is the average temperature measured at a particular cross-section of the pipe.

Newton’s Law of Cooling

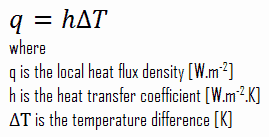

Despite the complexity of convection, the rate of convection heat transfer is observed to be proportional to the temperature difference and is conveniently expressed by Newton’s law of cooling, which states that:

The rate of heat loss of a body is directly proportional to the difference in the temperatures between the body and its surroundings provided the temperature difference is small and the nature of radiating surface remains same.

Note that, ΔT is given by the surface or wall temperature, Twall and the bulk temperature, T∞, which is the temperature of the fluid sufficiently far from the surface.

Convective Heat Transfer Coefficient

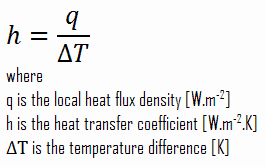

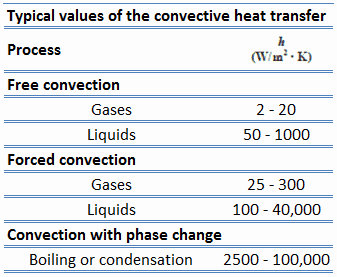

As can be seen, the constant of proportionality will be crucial in calculations and it is known as the convective heat transfer coefficient, h. The convective heat transfer coefficient, h, can be defined as:

The rate of heat transfer between a solid surface and a fluid per unit surface area per unit temperature difference.

Typically, the convective heat transfer coefficient for laminar flow is relatively low compared to the convective heat transfer coefficient for turbulent flow. This is due to turbulent flow having a thinner stagnant fluid film layer on the heat transfer surface.

It must be noted, this stagnant fluid film layer plays crucial role for the convective heat transfer coefficient. It is observed, that the fluid comes to a complete stop at the surface and assumes a zero velocity relative to the surface. This phenomenon is known as the no-slip condition and therefore, at the surface, energy flow occurs purely by conduction. But in the next layers both conduction and diffusion-mass movement in the molecular level or macroscopic level occurs. Due to the mass movement the rate of energy transfer is higher. As was written, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer and therefore nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to bulk fluid.

A similar phenomenon occurs for the temperature. It is observed, that the fluid’s temperature at the surface and the surface will have the same temperature at the point of contact. This phenomenon is known as the no-temperature-jump condition and it is very important for theory of nucleate boiling.

Values of the heat transfer coefficient, h, have been measured and tabulated for the commonly encountered fluids and flow situations occurring during heat transfer by convection.

Nusselt Number

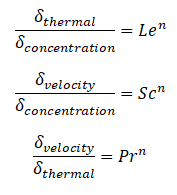

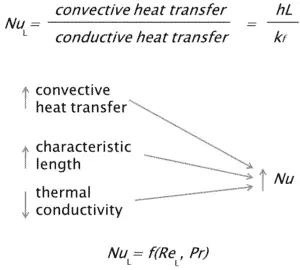

The Nusselt number is a dimensionless number, named after a German engineer Wilhelm Nusselt. The Nusselt number is closely related to Péclet number and both numbers are used to describe the ratio of the thermal energy convected to the fluid to the thermal energy conducted within the fluid. Nusselt number is equal to the dimensionless temperature gradient at the surface, and it provides a measure of the convection heat transfer occurring at the surface. The conductive component is measured under the same conditions as the heat convection but with a stagnant fluid. The Nusselt number is to the thermal boundary layer what the friction coefficient is to the velocity boundary layer. Thus, the Nusselt number is defined as:

where:

kf is thermal conductivity of the fluid [W/m.K]

L is the characteristic length

h is the convective heat transfer coefficient [W/m2.K]

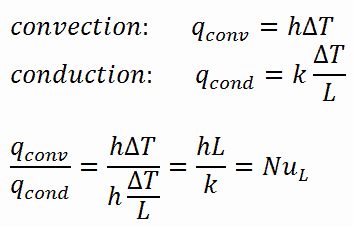

For illustration, consider a fluid layer of thickness L and temperature difference ΔT. Heat transfer through the fluid layer will be by convection when the fluid involves some motion and by conduction when the fluid layer is motionless.

In case of conduction, the heat flux can be calculated using Fourier’s law of conduction. In case of convection, the heat flux can be calculated using Newton’s law of cooling. Taking their ratio gives:

The preceding equation defines the Nusselt number. Therefore, the Nusselt number represents the enhancement of heat transfer through a fluid layer as a result of convection relative to conduction across the same fluid layer. A Nusselt number of Nu=1 for a fluid layer represents heat transfer across the layer by pure conduction. The larger the Nusselt number, the more effective the convection. A larger Nusselt number corresponds to more effective convection, with turbulent flow typically in the 100–1000 range. For turbulent flow, the Nusselt number is usually a function of the Reynolds number and the Prandtl number.

Example – Convective Heat Transfer – Cladding Surface Temperature

Cladding is the outer layer of the fuel rods, standing between the reactor coolant and the nuclear fuel (i.e. fuel pellets). It is made of a corrosion-resistant material with low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, usually zirconium alloy. Cladding prevents radioactive fission products from escaping the fuel matrix into the reactor coolant and contaminating it. Cladding constitute one of barriers in ‘defence-in-depth‘ approach, therefore its coolability is one of key safety aspects.

Cladding is the outer layer of the fuel rods, standing between the reactor coolant and the nuclear fuel (i.e. fuel pellets). It is made of a corrosion-resistant material with low absorption cross section for thermal neutrons, usually zirconium alloy. Cladding prevents radioactive fission products from escaping the fuel matrix into the reactor coolant and contaminating it. Cladding constitute one of barriers in ‘defence-in-depth‘ approach, therefore its coolability is one of key safety aspects.

Consider the fuel cladding of inner radius rZr,2 = 0.408 cm and outer radius rZr,1 = 0.465 cm. In comparison to fuel pellet, there is almost no heat generation in the fuel cladding (cladding is slightly heated by radiation). All heat generated in the fuel must be transferred via conduction through the cladding and therefore the inner surface is hotter than the outer surface.

Assume that:

- the outer diameter of the cladding is: d = 2 x rZr,1 = 9,3 mm

- the pitch of fuel pins is: p = 13 mm

- the thermal conductivity of saturated water at 300°C is: kH2O = 0.545 W/m.K

- the dynamic viscosity of saturated water at 300°C is: μ = 0.0000859 N.s/m2

- the fluid density is: ρ = 714 kg/m3

- the specific heat is: cp = 5.65 kJ/kg.K

- the core flow velocity is constant and equal to Vcore = 5 m/s

- the temperature of reactor coolant at this axial coordinate is: Tbulk = 296°C

- the linear heat rate of the fuel is qL = 300 W/cm (FQ ≈ 2.0) and thus the volumetric heat rate is qV = 597 x 106 W/m3

Calculate the Prandtl, Reynolds and Nusselt number for this flow regime (internal forced turbulent flow) inside the rectangular fuel lattice (fuel channel), then calculate the heat transfer coefficient and finally the cladding surface temperature, TZr,1.

Calculate the Prandtl, Reynolds and Nusselt number for this flow regime (internal forced turbulent flow) inside the rectangular fuel lattice (fuel channel), then calculate the heat transfer coefficient and finally the cladding surface temperature, TZr,1.

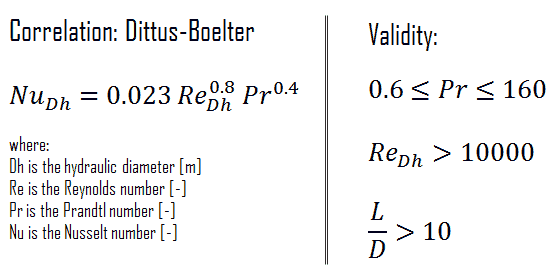

To calculate the cladding surface temperature, we have to calculate the Prandtl, Reynolds and Nusselt number, because the heat transfer for this flow regime can be described by the Dittus-Boelter equation, which is:

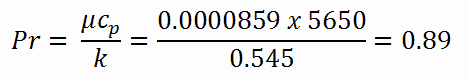

Calculation of the Prandtl number

To calculate the Prandtl number, we have to know:

- the thermal conductivity of saturated water at 300°C is: kH2O = 0.545 W/m.K

- the dynamic viscosity of saturated water at 300°C is: μ = 0.0000859 N.s/m2

- the specific heat is: cp = 5.65 kJ/kg.K

Note that, all these parameters significantly differs for water at 300°C from those at 20°C. Prandtl number for water at 20°C is around 6.91. Prandtl number for reactor coolant at 300°C is then:

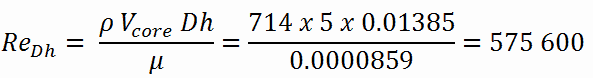

Calculation of the Reynolds number

To calculate the Reynolds number, we have to know:

- the outer diameter of the cladding is: d = 2 x rZr,1 = 9,3 mm (to calculate the hydraulic diameter)

- the pitch of fuel pins is: p = 13 mm (to calculate the hydraulic diameter)

- the dynamic viscosity of saturated water at 300°C is: μ = 0.0000859 N.s/m2

- the fluid density is: ρ = 714 kg/m3

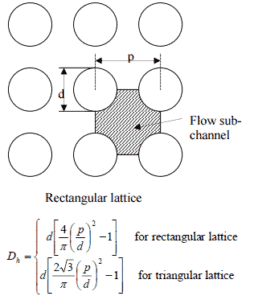

The hydraulic diameter, Dh, is a commonly used term when handling flow in non-circular tubes and channels. The hydraulic diameter of the fuel channel, Dh, is equal to 13,85 mm.

See also: Hydraulic Diameter

The Reynolds number inside the fuel channel is then equal to:

This fully satisfies the turbulent conditions.

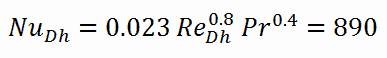

Calculation of the Nusselt number using Dittus-Boelter equation

For fully developed (hydrodynamically and thermally) turbulent flow in a smooth circular tube, the local Nusselt number may be obtained from the well-known DittusBoelter equation.

To calculate the Nusselt number, we have to know:

- the Reynolds number, which is ReDh = 575600

- the Prandtl number, which is Pr = 0.89

The Nusselt number for the forced convection inside the fuel channel is then equal to:

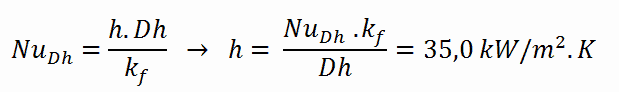

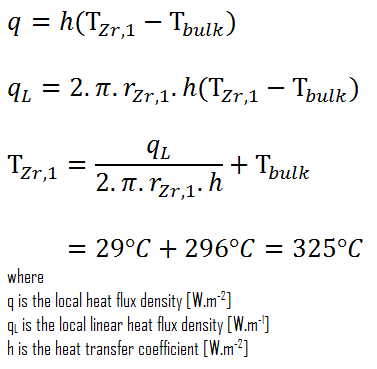

Calculation of the heat transfer coefficient and the cladding surface temperature, TZr,1

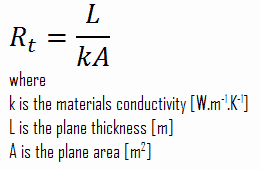

Detailed knowledge of geometry, fluid parameters, outer radius of cladding, linear heat rate, convective heat transfer coefficient allows us to calculate the temperature difference ∆T between the coolant (Tbulk) and the cladding surface (TZr,1).

To calculate the the cladding surface temperature, we have to know:

- the outer diameter of the cladding is: d = 2 x rZr,1 = 9,3 mm

- the Nusselt number, which is NuDh = 890

- the hydraulic diameter of the fuel channel is: Dh = 13,85 mm

- the thermal conductivity of reactor coolant (300°C) is: kH2O = 0.545 W/m.K

- the bulk temperature of reactor coolant at this axial coordinate is: Tbulk = 296°C

- the linear heat rate of the fuel is: qL = 300 W/cm (FQ ≈ 2.0)

The convective heat transfer coefficient, h, is given directly by the definition of Nusselt number:

Finally, we can calculate the cladding surface temperature (TZr,1) simply using the Newton’s Law of Cooling:

For PWRs at normal operation, there is a compressed liquid water inside the reactor core, loops and steam generators. The pressure is maintained at approximately 16MPa. At this pressure water boils at approximately 350°C(662°F). As can be seen, the surface temperature TZr,1 = 325°C ensures, that even subcooled boiling does not occur. Note that, subcooled boiling requires TZr,1 = Tsat. Since the inlet temperatures of the water are usually about 290°C (554°F), it is obvious this example corresponds to the lower part of the core. At higher elevations of the core the bulk temperature may reach up to 330°C. The temperature difference of 29°C causes the subcooled boiling may occur (330°C + 29°C > 350°C). On the other hand, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts the stagnant layer and therefore nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to bulk fluid. As a result, the convective heat transfer coefficient significantly increases and therefore at higher elevations, the temperature difference (TZr,1 – Tbulk) significantly decreases.

We hope, this article, Convection – Convective Heat Transfer, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.