Thermodynamic Properties

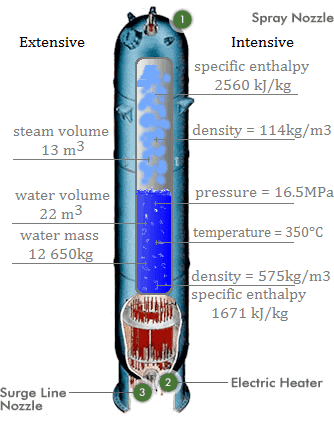

Within thermodynamics, a physical property is any property that is measurable, and whose value describes a state of a physical system. Our goal here will be to introduce thermodynamic properties, that are used in engineering thermodynamics. These properties will be further applied to energy systems and finally to thermal or nuclear power plants.

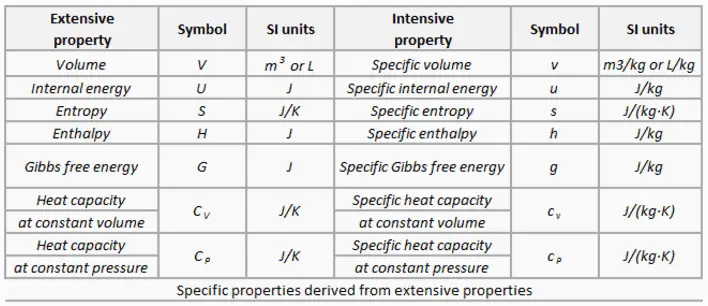

In general, thermodynamic properties can be divided into two general classes:

- Extensive properties: An extensive property is dependent upon the amount of mass present or upon the size or extent of a system. For example, the following properties are extensive:

- Intensive property: An intensive property is independent of the amount of mass and may vary from place to place within the system at any moment. For example, the following properties are extensive:

- Compressibility

- Density

- Specific Enthalpy

- Specific Entropy

- Specific Heat Capacity

- Pressure

- Temperature

- Thermal Conductivity

- Thermal Expansion

- Vapor Quality

- Specific Volume

Specific Properties

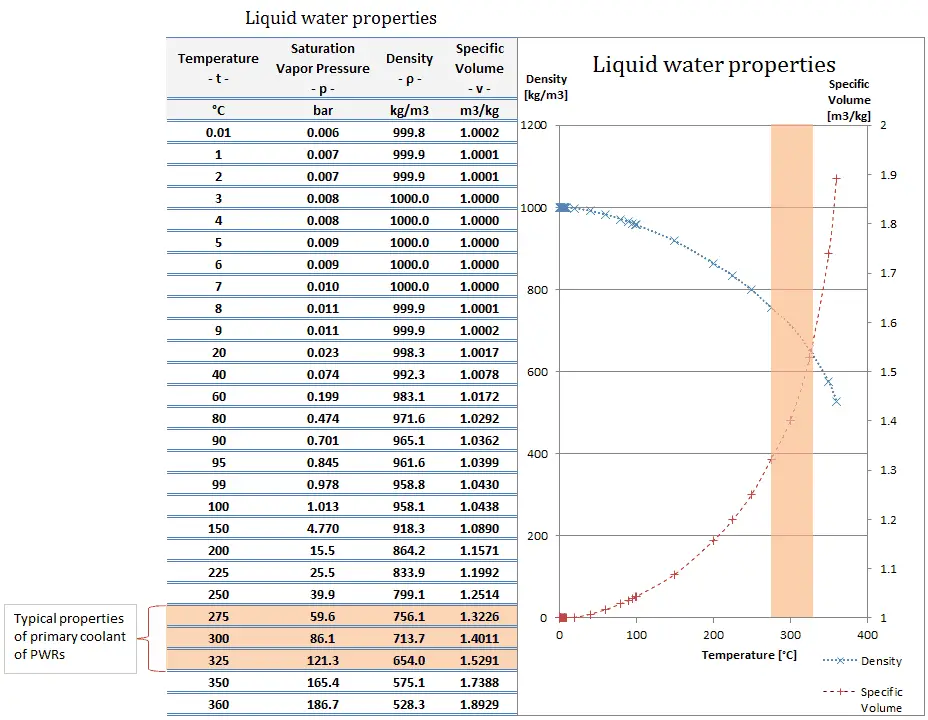

Specific properties of material are derived from other intensive and extensive properties of that material. For example, the density of water is an intensive property and can be derived from measurements of the mass of a water volume (an extensive property) divided by the volume (another extensive property). Also heat capacity, which is an extensive property of a system can be derived from heat capacity, Cp, and the mass of the system. Dividing these extensive properties gives the specific heat capacity, cp, which is an intensive property.

Specific properties are often used in reference tables as a means of recording material data in a manner that is independent of size or mass. They are very useful for making comparisons about one attribute while cancelling out the effect of variations in another attribute.

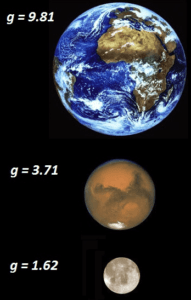

Mass vs. Weight

One of the most familiar forces is the weight of a body, which is the gravitational force that the earth exerts on the body. In general, gravitation is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass are brought toward one another. The terms mass and weight are often confused with one another, but it is important to distinguish between them. It is absolutely essential to understand clearly the distinctions between these two physical quantities.

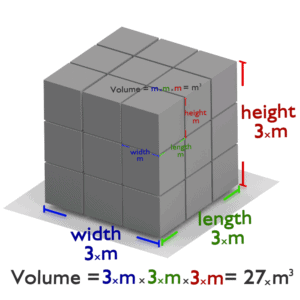

What is Volume

Volume is a basic physical quantity. Volume is a derived quantity and it expresses the three dimensional extent of an object. Volume is often quantified numerically using the SI derived unit, the cubic metre. For example, the volume inside a sphere (that is the volume of a ball) is derived to be V = 4/3πr3, where r is the radius of the sphere. As another example, volume of a cube is equal to side times side times side. Since each side of a square is the same, it can simply be the length of one side cubed.

Volume is a basic physical quantity. Volume is a derived quantity and it expresses the three dimensional extent of an object. Volume is often quantified numerically using the SI derived unit, the cubic metre. For example, the volume inside a sphere (that is the volume of a ball) is derived to be V = 4/3πr3, where r is the radius of the sphere. As another example, volume of a cube is equal to side times side times side. Since each side of a square is the same, it can simply be the length of one side cubed.

If a square has one side of 3 metres, the volume would be 3 metres times 3 metres times 3 metres, or 27 cubic metres.

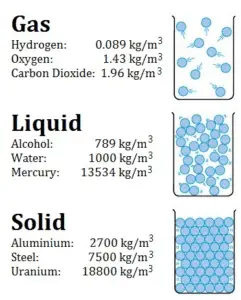

What is Density

Density is defined as the mass per unit volume. It is an intensive property, which is mathematically defined as mass divided by volume:

ρ = m/V

In words, the density (ρ) of a substance is the total mass (m) of that substance divided by the total volume (V) occupied by that substance. The standard SI unit is kilograms per cubic meter (kg/m3). The Standard English unit is pounds mass per cubic foot (lbm/ft3). The density (ρ) of a substance is the reciprocal of its specific volume (ν).

ρ = m/V = 1/ρ

Specific volume is an intensive variable, whereas volume is an extensive variable. The standard unit for specific volume in the SI system is cubic meters per kilogram (m3/kg). The standard unit in the English system is cubic feet per pound mass (ft3/lbm).

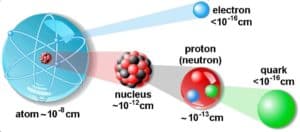

Density of Nuclear Matter

Nuclear density is the density of the nucleus of an atom. It is the ratio of mass per unit volume inside the nucleus. Since atomic nucleus carries most of atom’s mass and atomic nucleus is very small in comparison to entire atom, the nuclear density is very high.

The nuclear density for a typical nucleus can be approximately calculated from the size of the nucleus and from its mass. Typical nuclear radii are of the order 10−14 m. Assuming spherical shape, nuclear radii can be calculated according to following formula:

r = r0 . A1/3

where r0 = 1.2 x 10-15 m = 1.2 fm

For example, natural uranium consists primarily of isotope 238U (99.28%), therefore the atomic mass of uranium element is close to the atomic mass of 238U isotope (238.03u). Its radius of this nucleus will be:

r = r0 . A1/3 = 7.44 fm.

Assuming it is spherical, its volume will be:

V = 4πr3/3 = 1.73 x 10-42 m3.

The usual definition of nuclear density gives for its density:

ρnucleus = m / V = 238 x 1.66 x 10-27 / (1.73 x 10-42) = 2.3 x 1017 kg/m3.

Thus, the density of nuclear material is more than 2.1014 times greater than that of water. It is an immense density. The descriptive term nuclear density is also applied to situations where similarly high densities occur, such as within neutron stars. Such immense densities are also found in neutron stars.

What is Pressure

Pressure is a measure of the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance. The standard unit for pressure in the SI system is the Newton per square meter or pascal (Pa). Mathematically:

Pressure is a measure of the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance. The standard unit for pressure in the SI system is the Newton per square meter or pascal (Pa). Mathematically:

p = F/A

where

- p is the pressure

- F is the normal force

- A is the area of the boundary

Pascal is defined as force of 1N that is exerted on unit area.

- 1 Pascal = 1 N/m2

- 1 MPa 106 N/m2

- 1 bar 105 N/m2

- 1 kPa 103 N/m2

In general, pressure or the force exerted per unit area on the boundaries of a substance is caused by the collisions of the molecules of the substance with the boundaries of the system. As molecules hit the walls, they exert forces that try to push the walls outward. The forces resulting from all of these collisions cause the pressure exerted by a system on its surroundings. Pressure as an intensive variable is constant in a closed system. It really is only relevant in liquid or gaseous systems.

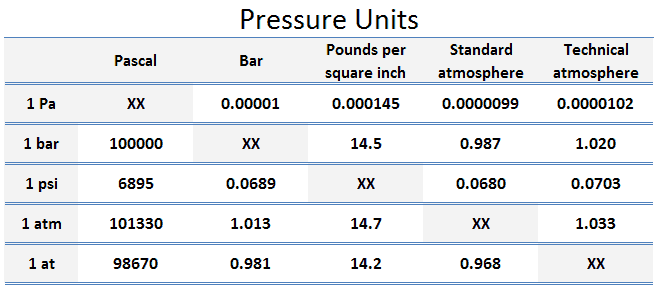

Pressure Scales – Pressure Units

Pascal – Unit of Pressure

As was discussed, the SI unit of pressure and stress is the pascal.

- 1 pascal 1 N/m2 = 1 kg / (m.s2)

Pascal is defined as one newton per square metre. However, for most engineering problems it is fairly small unit, so it is convenient to work with multiples of the pascal: the kPa, the bar, and the MPa.

- 1 MPa 106 N/m2

- 1 bar 105 N/m2

- 1 kPa 103 N/m2

The unit of measurement called standard atmosphere (atm) is defined as:

- 1 atm = 101.33 kPa

The standard atmosphere approximates to the average pressure at sea-level at the latitude 45° N. Note that, there is a difference between the standard atmosphere (atm) and the technical atmosphere (at).

A technical atmosphere is a non-SI unit of pressure equal to one kilogram-force per square centimeter.

- 1 at = 98.67 kPa

See also: Pound per square inch – psi

See also: Bar – Unit of Pressure

See also: Typical Pressures in Engineering

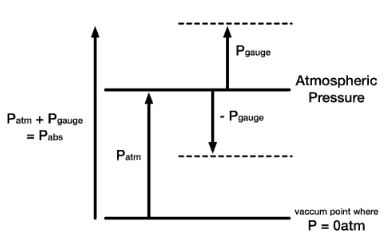

Absolute vs. Gauge Pressure

- Absolute Pressure. When pressure is measured relative to a perfect vacuum, it is called absolute pressure (psia). Pounds per square inch absolute (psia) is used to make it clear that the pressure is relative to a vacuum rather than the ambient atmospheric pressure. Since atmospheric pressure at sea level is around 101.3 kPa (14.7 psi), this will be added to any pressure reading made in air at sea level.

- Gauge Pressure. When pressure is measured relative to atmospheric pressure (14.7 psi), it is called gauge pressure (psig). The term gauge pressure is applied when the pressure in the system is greater than the local atmospheric pressure, patm. The latter pressure scale was developed because almost all pressure gauges register zero when open to the atmosphere. Gauge pressures are positive if they are above atmospheric pressure and negative if they are below atmospheric pressure.

pgauge = pabsolute – pabsolute; atm

- Atmospheric Pressure. Atmospheric pressure is the pressure in the surrounding air at – or “close” to – the surface of the earth. The atmospheric pressure varies with temperature and altitude above sea level. The Standard Atmospheric Pressure approximates to the average pressure at sea-level at the latitude 45° N. The Standard Atmospheric Pressure is defined at sea-level at 273oK (0oC) and is:

- 101325 Pa

- 1.01325 bar

- 14.696 psi

- 760 mmHg

- 760 torr

- Negative Gauge Pressure – Vacuum Pressure. When the local atmospheric pressure is greater than the pressure in the system, the term vacuum pressure is used. A perfect vacuum would correspond to absolute zero pressure. It is certainly possible to have a negative gauge pressure, but not possible to have a negative absolute pressure. For instance, an absolute pressure of 80 kPa may be described as a gauge pressure of −21 kPa (i.e., 21 kPa below an atmospheric pressure of 101 kPa).

pvacuum = pabsolute; atm – pabsolute

For example, a car tire pumped up to 2.5 atm (36.75 psig) above local atmospheric pressure (let say 1 atm or 14.7 psia locally), will have an absolute pressure of 2.5 + 1 = 3.5 atm (36.75 + 14.7 = 51.45 psia or 36.75 psig).

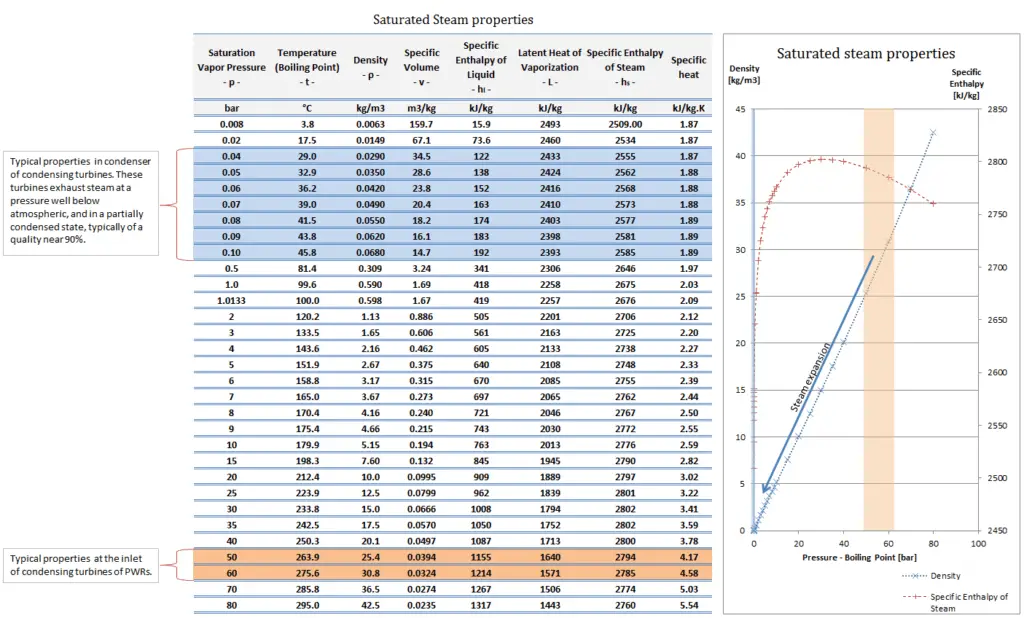

On the other hand condensing steam turbines (at nuclear power plants) exhaust steam at a pressure well below atmospheric (e.g. at 0.08 bar or 8 kPa or 1.16 psia) and in a partially condensed state. In relative units it is a negative gauge pressure of about – 0.92 bar, – 92 kPa, or – 13.54 psig.

Typical Pressures in Engineering – Examples

The pascal (Pa) as a unit of pressure measurement is widely used throughout the world and has largely replaced the pounds per square inch (psi) unit, except in some countries that still use the Imperial measurement system, including the United States. For most engineering problems pascal (Pa) is fairly small unit, so it is convenient to work with multiples of the pascal: the kPa, the MPa, or the bar. Following list summarizes a few examples:

- Typically most of nuclear power plants operates multi-stage condensing steam turbines. These turbines exhaust steam at a pressure well below atmospheric (e.g. at 0.08 bar or 8 kPa or 1.16 psia) and in a partially condensed state. In relative units it is a negative gauge pressure of about – 0.92 bar, – 92 kPa, or – 13.54 psig.

- The Standard Atmospheric Pressure approximates to the average pressure at sea-level at the latitude 45° N. The Standard Atmospheric Pressure is defined at sea-level at 273oK (0oC) and is:

- 101325 Pa

- 1.01325 bar

- 14.696 psi

- 760 mmHg

- 760 torr

- Car tire overpressure is about 2.5 bar, 0.25 MPa, or 36 psig.

- Steam locomotive fire tube boiler: 150–250 psig

- A high-pressure stage of condensing steam turbine at nuclear power plant operates at steady state with inlet conditions of 6 MPa (60 bar, or 870 psig), t = 275.6°C, x = 1

- A boiling water reactor is cooled and moderated by water like a PWR, but at a lower pressure (e.g. 7MPa, 70 bar, or 1015 psig), which allows the water to boil inside the pressure vessel producing the steam that runs the turbines.

- Pressurized water reactors are cooled and moderated by high-pressure liquid water (e.g. 16MPa, 160 bar, or 2320 psig). At this pressure water boils at approximately 350°C (662°F), which provides subcooling margin of about 25°C.

- The supercritical water reactor (SCWR) is operated at supercritical pressure. The term supercritical in this context refers to the thermodynamic critical point of water (TCR = 374 °C; pCR = 22.1 MPa)

- Common rail direct fuel injection: On diesel engines, it features a high-pressure (over 1 000 bar or 100 MPa or 14500 psi) fuel rail.

What is Temperature

In physics and in everyday life a temperature is an objective comparative measurement of hot or cold based on our sense of touch. A body that feels hot usually has a higher temperature than a similar body that feels cold. But this definition is not a simple matter. For example, a metal rod feels colder than a plastic rod at room temperature simply because metals are generally better at conducting heat away from the skin as are plastics. Simply hotness may be represented abstractly and therefore it is necessary to have an objective way of measuring temperature. It is one of basic thermodynamic properties.

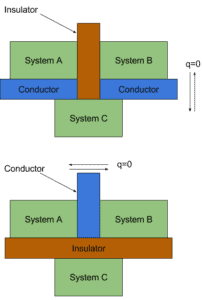

Thermal Equilibrium

A particularly important concept is thermodynamic equilibrium. In general, when two objects are brought into thermal contact, heat will flow between them until they come into equilibrium with each other. When a temperature difference does exist heat flows spontaneously from the warmer system to the colder system. Heat transfer occurs by conduction or by thermal radiation. When the flow of heat stops, they are said to be at the same temperature. They are then said to be in thermal equilibrium.

For example, you leave a thermometer in a cup of coffee. As the two objects interact, the thermometer becomes hotter and the coffee cools off a little until they come into thermal equilibrium. Two objects are defined to be in thermal equilibrium if, when placed in thermal contact, no net energy flows from one to the other, and their temperatures don’t change. We may postulate:

When the two objects are in thermal equilibrium, their temperatures are equal.

This is a subject of a law that is called the “zeroth law of thermodynamics”.

For example, most materials expand when their temperature is increased. This property is very important in all of the science and engineering, even in nuclear engineering. The thermodynamic efficiency of power plants changes with temperature of inlet steam or even with outside temperature. At higher temperatures, solids such as steel glow orange or even white depending on temperature. The white light from an ordinary incandescent lightbulb comes from an extremely hot tungsten wire. It can be seen temperature is one of the fundamental characteristics that describes matter and influences matter behaviour.

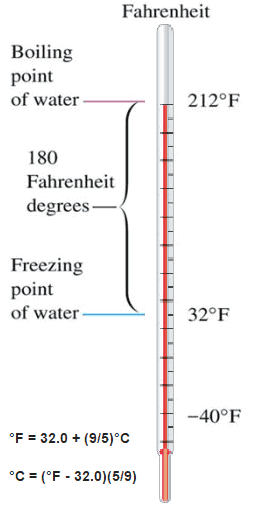

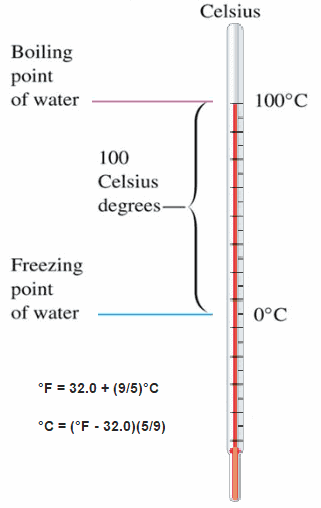

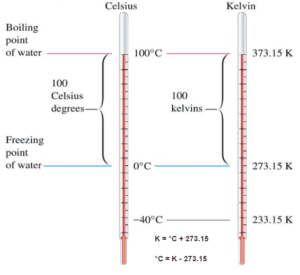

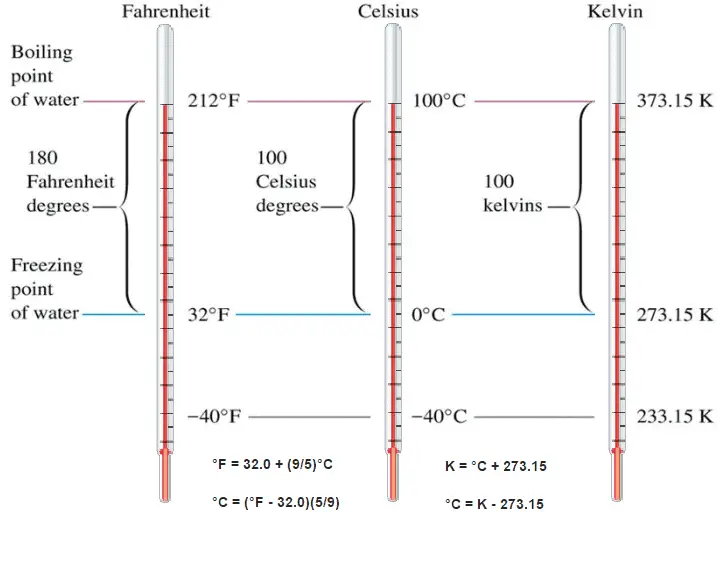

Temperature Scales

These numbers are arbitrary, and historically many different schemes have been used. For example, this was done by defining some physical occurrences at given temperatures—such as the freezing and boiling points of water — and defining them as 0 and 100 respectively.

There are several scales and units exist for measuring temperature. The most common are:

- Celsius (denoted °C),

- Fahrenheit (denoted °F),

- Kelvin (denoted K; especially in science).

We hope, this article, Thermodynamic Property, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.