What is Weight

One of the most familiar forces is the weight of a body, which is the gravitational force that the earth exerts on the body. In general, gravitation is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass are brought toward one another. The terms mass and weight are often confused with one another, but it is important to distinguish between them. It is absolutely essential to understand clearly the distinctions between these two physical quantities.

The terms are often confused with one another, but it is important to distinguish between them. In science and engineering, the weight of an object is usually taken to be the force on the object due to gravity. In general, gravitation is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass are brought toward one another.The mass of an object is a fundamental property of the object. It is a numerical measure of its inertia and the measure of an object’s resistance to acceleration when a force is applied. It is also a fundamental measure of the amount of matter in the object. The greater the mass, the greater the force needed to cause a given acceleration. This is reflected in Newton’s second law (F=ma).

The mass of a certain body will remain constant even if the gravitational acceleration acting upon that body changes. For example, on earth an object has a certain mass and a certain weight. When the same object is placed in outer space, away from the earth’s gravitational field, its mass remains the same, but it is now in a “weightless” condition. This means in this condition it will weight zero, because gravitational acceleration and, thus, force will equal to zero.

Mass and weight are related:

Bodies having large mass also have large weight. A large stone is hard to throw because of its large mass, and hard to lift off the ground because of its large weight. To understand the relationship between mass and weight, consider a freely falling stone, that has an acceleration of magnitude g (g = 9.81 m/s2 is the acceleration due to Earth’s gravitational field). Newton’s second law tells us that a force must act to produce this acceleration. If a 1 kilogram stone falls with an acceleration of the required force has magnitude:

F = ma = 1 [kg] x 9.81 [m/s2] = 9.8 [kg m/s2] = 9.8 N

The force that makes the body accelerate downward is its weight. Any body near the surface of the earth that has a mass of 1 kg must have a weight of 9.8 N to give it the acceleration we observe when it is in free fall.

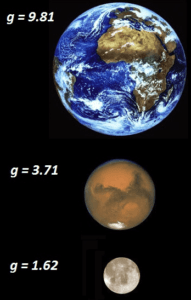

Example: The weight of a stone on the Earth, on the Mars and on the Moon

Weight of a stone on the Earth

The acceleration due to Earth’s gravitational field is gEarth = 9.81 m/s2.The weight of a stone with mass 1 kg on the Earth can be calculated as:

The acceleration due to Earth’s gravitational field is gEarth = 9.81 m/s2.The weight of a stone with mass 1 kg on the Earth can be calculated as:

FEarth = 1 [kg] x 9.81 [m/s2] = 9.8 [kg m/s2] = 9.8 N

Weight of a stone on the Mars

The acceleration of gravity on the Mars is approximately 38% of the acceleration of gravity on the earth. The acceleration due to Moon’s gravitational field is gMars = 3.71 m/s2.

Therefore the weight of the same stone with mass 1 kg on the Mars is:

FMoon = 1 [kg] x 3.71 [m/s2] = 3.71 [kg m/s2] = 3.71 N

Weight of a stone on the Moon

The acceleration of gravity on the Moon is approximately 1/6 of the acceleration of gravity on the earth. The acceleration due to Moon’s gravitational field is gMoon = 1.62 m/s2.

Therefore the weight of the same stone with mass 1 kg on the Moon is:

FMoon = 1 [kg] x 1.62 [m/s2] = 1.62 [kg m/s2] = 1.62 N

We hope, this article, Weight, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.