Boiling

Source: wikipedia.org CC BY-SA

In preceding chapters, we have discussed convective heat transfer with very important assumption. We have assumed a single-phase convective heat transfer without any phase change. In this chapter we focus on convective heat transfer associated with the change in phase of a fluid. In particular, we consider processes that can occur at a solid–liquid or solid–vapor interface, namely, boiling (liquid-to-vapor phase change) and condensation (vapor-to-liquid phase change).

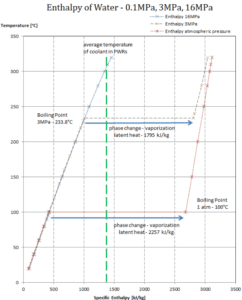

For these cases latent heat effects associated with the phase change are significant. Latent heat, known also as the enthalpy of vaporization, is the amount of heat added to or removed from a substance to produce a change in phase. This energy breaks down the intermolecular attractive forces, and also must provide the energy necessary to expand the gas (the pΔV work). When latent heat is added, no temperature change occurs.

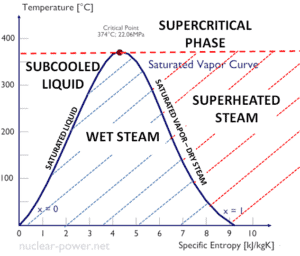

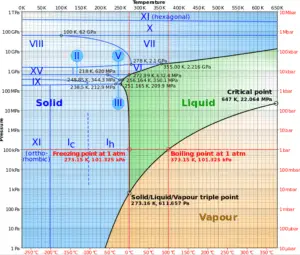

The enthalpy of vaporization is a function of the pressure at which that transformation takes place.

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 0.1 MPa (atmospheric pressure)

hlg = 2257 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 3 MPa

hlg = 1795 kJ/kg

Latent heat of vaporization – water at 16 MPa (pressure inside a pressurizer)

hlg = 931 kJ/kg

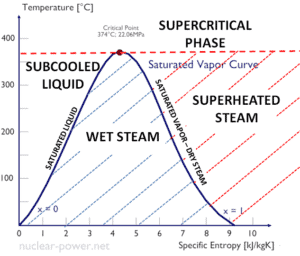

The heat of vaporization diminishes with increasing pressure, while the boiling point increases. It vanishes completely at a certain point called the critical point. Above the critical point, the liquid and vapor phases are indistinguishable, and the substance is called a supercritical fluid.

The change from the liquid to the vapor state due to boiling is sustained by heat transfer from the solid surface; conversely, condensation of a vapor to the liquid state results in heat transfer to the solid surface. Boiling and condensation differ from other forms of convection in that they depend on the latent heat of vaporization, which is very high for common pressures, therefore large amounts of heat can be transferred during boiling and condensation essentially at constant temperature. Heat transfer coefficients, h, associated with boiling and condensation are typically much higher than those encountered in other forms of convection processes that involve a single phase.

The change from the liquid to the vapor state due to boiling is sustained by heat transfer from the solid surface; conversely, condensation of a vapor to the liquid state results in heat transfer to the solid surface. Boiling and condensation differ from other forms of convection in that they depend on the latent heat of vaporization, which is very high for common pressures, therefore large amounts of heat can be transferred during boiling and condensation essentially at constant temperature. Heat transfer coefficients, h, associated with boiling and condensation are typically much higher than those encountered in other forms of convection processes that involve a single phase.

This is due to the fact, even in turbulent flow, there is a stagnant fluid film layer (laminar sublayer), that isolates the surface of the heat exchanger. This stagnant fluid film layer plays crucial role for the convective heat transfer coefficient. It is observed, that the fluid comes to a complete stop at the surface and assumes a zero velocity relative to the surface. This phenomenon is known as the no-slip condition and therefore, at the surface, energy flow occurs purely by conduction. But in the next layers both conduction and diffusion-mass movement in the molecular level or macroscopic level occurs. Due to the mass movement the rate of energy transfer is higher. As was written, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts this stagnant layer and therefore nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to bulk fluid.

Boiling Modes – Types of Boiling

From a practical engineering point of view boiling can be categorized according to several criteria.

From a practical engineering point of view boiling can be categorized according to several criteria.

Categorization by the flow regime:

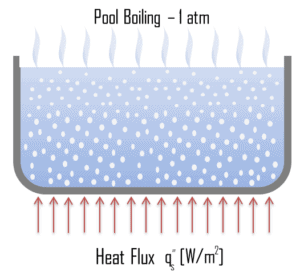

- Pool Boiling. Perhaps the most common configuration, known as pool boiling is when a pool of liquid is heated from below through a horizontal surface. In pool boiling the liquid is quiescent and its motion near the surface is primarily due to natural convection and to mixing induced by bubble growth and detachment. The pioneering work on pool boiling was done in 1934 by S. Nukiyama. He was the first to identify four well known different regimes of pool boiling using his apparatus.

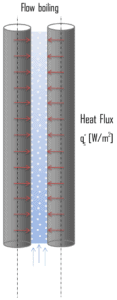

Flow Boiling. In flow boiling (or forced convection boiling), fluid flow is forced over a surface by external means such as a pump, as well as by buoyancy effects. Therefore, flow boiling is always accompanied by other convection effects. Conditions depend strongly on geometry, which may involve external flow over heated plates and cylinders or internal (duct) flow. In nuclear reactors, most of boiling regimes are just forced convection boiling.

Flow Boiling. In flow boiling (or forced convection boiling), fluid flow is forced over a surface by external means such as a pump, as well as by buoyancy effects. Therefore, flow boiling is always accompanied by other convection effects. Conditions depend strongly on geometry, which may involve external flow over heated plates and cylinders or internal (duct) flow. In nuclear reactors, most of boiling regimes are just forced convection boiling.

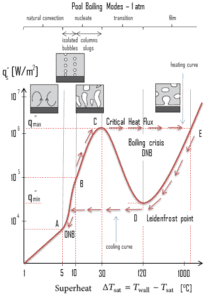

Categorization by the wall superheat temperature, ΔTsat:

The pioneering work on boiling was done in 1934 by S. Nukiyama, who used electrically heated nichrome and platinum wires immersed in liquids in his experiments. Nukiyama was the first to identify different regimes of pool boiling using his apparatus. He noticed that boiling takes different forms, depending on the value of the wall superheat temperature ΔTsat (known also as the excess temperature), which is defined as the difference between the wall temperature, Twall and the saturation temperature, Tsat.

The pioneering work on boiling was done in 1934 by S. Nukiyama, who used electrically heated nichrome and platinum wires immersed in liquids in his experiments. Nukiyama was the first to identify different regimes of pool boiling using his apparatus. He noticed that boiling takes different forms, depending on the value of the wall superheat temperature ΔTsat (known also as the excess temperature), which is defined as the difference between the wall temperature, Twall and the saturation temperature, Tsat.

Four different boiling regimes of pool boiling (based on the excess temperature) are observed:

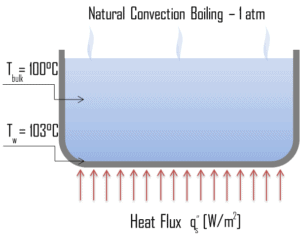

- Natural Convection Boiling ΔTsat < 5°C

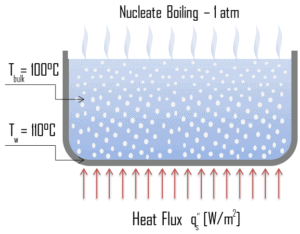

- Nucleate Boiling 5°C < ΔTsat < 30°C

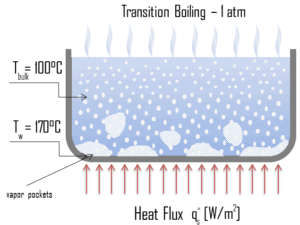

- Transition Boiling 30°C < ΔTsat < 200°C

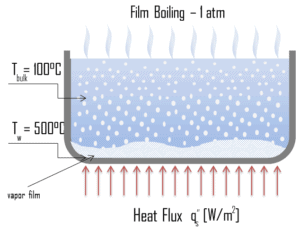

- Film Boiling 200°C < ΔTsat

Description of Boiling Modes:

Natural Convection Boiling. In thermodynamics, the requirement for boiling of pure substances to occur is that Twall = Tsat. But in real experiments, boiling does not occur until the liquid is heated a few degrees above the saturation temperature. The surface temperature must be somewhat above the saturation temperature in order to sustain vapor formation. In this boiling mode, vapour will be observed over the water surface, but usually no bubbles will be observed. As the superheat temperature is increased, bubble inception will eventually occur, but below point A, fluid motion is determined principally by natural convection currents. The point A is usually referred to as the onset of nucleate boiling – ONB.

Natural Convection Boiling. In thermodynamics, the requirement for boiling of pure substances to occur is that Twall = Tsat. But in real experiments, boiling does not occur until the liquid is heated a few degrees above the saturation temperature. The surface temperature must be somewhat above the saturation temperature in order to sustain vapor formation. In this boiling mode, vapour will be observed over the water surface, but usually no bubbles will be observed. As the superheat temperature is increased, bubble inception will eventually occur, but below point A, fluid motion is determined principally by natural convection currents. The point A is usually referred to as the onset of nucleate boiling – ONB. Nucleate Boiling. The most common type of local boiling encountered in nuclear facilities is nucleate boiling. In nucleate boiling, steam bubbles form at the heat transfer surface and then break away and are carried into the main stream of the fluid. Such movement enhances heat transfer because the heat generated at the surface is carried directly into the fluid stream. Once in the main fluid stream, the bubbles collapse because the bulk temperature of the fluid is not as high as the heat transfer surface temperature where the bubbles were created. This heat transfer process is sometimes desirable because the energy created at the heat transfer surface is quickly and efficiently “carried” away.

Nucleate Boiling. The most common type of local boiling encountered in nuclear facilities is nucleate boiling. In nucleate boiling, steam bubbles form at the heat transfer surface and then break away and are carried into the main stream of the fluid. Such movement enhances heat transfer because the heat generated at the surface is carried directly into the fluid stream. Once in the main fluid stream, the bubbles collapse because the bulk temperature of the fluid is not as high as the heat transfer surface temperature where the bubbles were created. This heat transfer process is sometimes desirable because the energy created at the heat transfer surface is quickly and efficiently “carried” away. Transition Boiling. The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely. At some value, we call it the “critical heat flux” (CHF), the steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient. This is because a large fraction of the surface is covered by a vapor film, which acts as an thermal insulation due to the low thermal conductivity of the vapor relative to that of the liquid. Immediately after the critical heat flux has been reached, boiling become unstable and transition boiling occurs. The transition from nucleate boiling to film boiling is known as the “boiling crisis”. Since beyond the CHF point the heat transfer coefficient decreases, the transition to film boiling is usually inevitable.

Transition Boiling. The nucleate boiling heat flux cannot be increased indefinitely. At some value, we call it the “critical heat flux” (CHF), the steam produced can form an insulating layer over the surface, which in turn deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient. This is because a large fraction of the surface is covered by a vapor film, which acts as an thermal insulation due to the low thermal conductivity of the vapor relative to that of the liquid. Immediately after the critical heat flux has been reached, boiling become unstable and transition boiling occurs. The transition from nucleate boiling to film boiling is known as the “boiling crisis”. Since beyond the CHF point the heat transfer coefficient decreases, the transition to film boiling is usually inevitable. Film Boiling. A further increase in the heat flux causes a film of vapour to cover the surface. This significantly reduces the convection coefficient, since the vapor layer has significantly lower heat transfer ability. As a result the excess temperature shoots up to a very high value. Beyond the Leidenfrost point, a continuous vapor film blankets the surface and there is no contact between the liquid phase and the surface. In this situation the heat transfer is both by radiation and by conduction to the vapour. If the material is not strong enough for withstanding this temperature, the equipment will fail by damage to the material. This phenomenon is also known as burn out. In pressurized water reactors, one of key safety requirements (maybe the most important) is that a departure from nucleate boiling (DNB) will not occur during steady state operation, normal operational transients, and anticipated operational occurrences (AOOs). Fuel cladding integrity will be maintained if the minimum DNBR remains above the 95/95 DNBR limit for PWRs ( a 95% probability at a 95% confidence level). Since this phenomenon deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient and the heat flux remains, heat then accumulates in the fuel rod causing dramatic rise of cladding and fuel temperature. Simply, a very high temperature difference is required to transfer the critical heat flux being produced from the surface of the fuel rod to the reactor coolant (through vapor layer).

Film Boiling. A further increase in the heat flux causes a film of vapour to cover the surface. This significantly reduces the convection coefficient, since the vapor layer has significantly lower heat transfer ability. As a result the excess temperature shoots up to a very high value. Beyond the Leidenfrost point, a continuous vapor film blankets the surface and there is no contact between the liquid phase and the surface. In this situation the heat transfer is both by radiation and by conduction to the vapour. If the material is not strong enough for withstanding this temperature, the equipment will fail by damage to the material. This phenomenon is also known as burn out. In pressurized water reactors, one of key safety requirements (maybe the most important) is that a departure from nucleate boiling (DNB) will not occur during steady state operation, normal operational transients, and anticipated operational occurrences (AOOs). Fuel cladding integrity will be maintained if the minimum DNBR remains above the 95/95 DNBR limit for PWRs ( a 95% probability at a 95% confidence level). Since this phenomenon deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient and the heat flux remains, heat then accumulates in the fuel rod causing dramatic rise of cladding and fuel temperature. Simply, a very high temperature difference is required to transfer the critical heat flux being produced from the surface of the fuel rod to the reactor coolant (through vapor layer).

Categorization by the subcooling temperature, ΔTsub.

Categorization by the subcooling temperature, ΔTsub.

Boiling may also be classified according to whether it is subcooled or saturated:

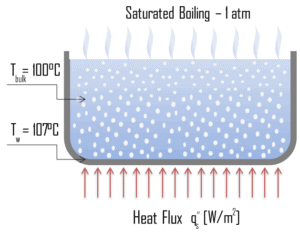

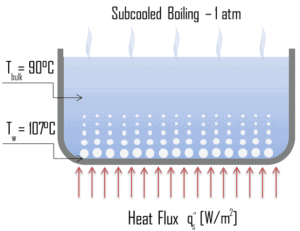

- Subcooled boiling. In subcooled boiling, the temperature of most of the liquid is below the saturation temperature and bubbles formed at the surface may condense in the liquid. This condensation (collapsing) produces a sound of frequency ~ 100Hz – 1 KHz. This is why an electric kettle makes the most noise before the water comes to saturated boiling. The term subcooling refers to a liquid existing at a temperature below its normal boiling point.

- Saturated Boiling. In saturated boiling (known also as bulk boiling), the temperature of the liquid slightly exceeds the saturation temperature. Bulk boiling may occur, when system temperature increases or system pressure drops to boiling point. At this point, the bubbles entering the coolant channel will not collapse. The bubbles will tend to join together and form bigger steam bubbles. Steam bubbles are then propelled through the liquid by buoyancy forces, eventually escaping from a free surface.

Boiling in Nuclear Reactors

Boiling in BWRs

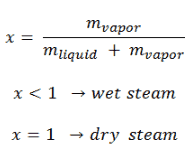

In BWRs boiling of coolant occurs at normal operation and it is very desired phenomenon. Typical flow qualities in BWR cores are on the order of 10 to 20 %. A boiling water reactor is cooled and moderated by water like a PWR, but at a lower pressure (7MPa), which allows the water to boil inside the pressure vessel producing the steam that runs the turbines. Evaporation therefore occurs directly in fuel channels. Therefore BWRs are the best example for this area, because evaporation of coolant occurs at normal operation and it is very desired phenomenon.

In BWRs there is a phenomenon, that is of the highest importance in reactor safety. This phenomenon is known as the “dryout” and it is directly associated with changes in flow pattern during evaporation in the high-quality region. At normal the fuel surface is effectively cooled by boiling coolant. However when the heat flux exceeds a critical value (CHF – critical heat flux) the flow pattern may reach the dryout conditions (thin film of liquid disappears). The heat transfer from the fuel surface into the coolant is deteriorated, with the result of a drastically increased fuel surface temperature.

Boiling in PWRs

Although the earliest core designs assumed that surface boiling could not be allowed in PWRs, this assumption was soon rejected and two-phase heat transfer is now one of normal operation heat transfer mechanisms also in PWRs. For PWRs at normal operation, there is a compressed liquid water inside the reactor core, loops and steam generators. The pressure is maintained at approximately 16MPa. At this pressure water boils at approximately 350°C(662°F). As was calculated in example, the surface temperature TZr,1 = 325°C ensures, that even subcooled boiling does not occur. Note that, subcooled boiling requires TZr,1 = Tsat. Since the inlet temperatures of the water are usually about 290°C (554°F), it is obvious this example corresponds to the lower part of the core. At higher elevations of the core the bulk temperature may reach up to 330°C. The temperature difference of 29°C causes the subcooled boiling may occur (330°C + 29°C > 350°C). On the other hand, nucleate boiling at the surface effectively disrupts the stagnant layer and therefore nucleate boiling significantly increases the ability of a surface to transfer thermal energy to bulk fluid. As a result, the convective heat transfer coefficient significantly increases and therefore at higher elevations, the temperature difference (TZr,1 – Tbulk) significantly decreases.

In case of PWRs, the critical safety issue is named DNB (departure from nucleate boiling), which causes the formation of a local vapor layer, causing a dramatic reduction in heat transfer capability. This phenomenon occurs in the subcooled or low-quality region. The behaviour of the boiling crisis depends on many flow conditions (pressure, temperature, flow rate), but the boiling crisis occurs at a relatively high heat fluxes and appears to be associated with the cloud of bubbles, adjacent to the surface. These bubbles or film of vapor reduces the amount of incoming water. Since this phenomenon deteriorates the heat transfer coefficient and the heat flux remains, heat then accumulates in the fuel rod causing dramatic rise of cladding and fuel temperature.

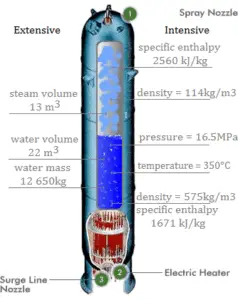

Saturation in Pressurizer

A pressurizer is a component of a pressurized water reactor. Pressure in the primary circuit of PWRs is maintained by a pressurizer, a separate vessel that is connected to the primary circuit (hot leg) and partially filled with water which is heated to the saturation temperature (boiling point) for the desired pressure by submerged electrical heaters. Temperature in the pressurizer can be maintained at 350 °C (662 °F), which gives a subcooling margin (the difference between the pressurizer temperature and the highest temperature in the reactor core) of 30 °C. Subcooling margin is very important safety parameter of PWRs, since the boiling in the reactor core must be excluded. The basic design of the pressurized water reactor includes such requirement that the coolant (water) in the reactor coolant system must not boil. To achieve this, the coolant in the reactor coolant system is maintained at a pressure sufficiently high that boiling does not occur at the coolant temperatures experienced while the plant is operating or in an analyzed transient.

Functions

Pressure in the pressurizer is controlled by varying the temperature of the coolant in the pressurizer. For these purposes two systems are installed. Water spray system and electrical heaters system. Volume of the pressurizer (tens of cubic meters) is filled with water on saturation parameters and steam. The water spray system (relatively cool water – from cold leg) can decrease the pressure in the vessel by condensing the steam on water droplets sprayed in the vessel. On the other hand the submerged electrical heaters are designed to increase the pressure by evaporation the water in the vessel. Water pressure in a closed system tracks water temperature directly; as the temperature goes up, pressure goes up.

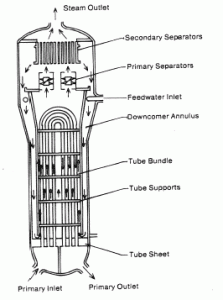

Boiling in Steam Generator

Steam generators are heat exchangers used to convert feedwater into steam from heat produced in a nuclear reactor core. The steam produced drives the turbine. They are used in the most nuclear power plants, but there are many types according to the reactor type.

The hot primary coolant (water 330°C; 626°F; 16MPa) is pumped into the steam generator through primary inlet. High pressure of primary coolant is used to keep the water in the liquid state. Boiling of the primary coolant shall not occur. The liquid water flows through hundreds or thousands of tubes (usually 1.9 cm in diameter) inside the steam generator. The feedwater (secondary circuit) is heated from ~260°C 500°F to the boiling point of that fluid (280°C; 536°F; 6,5MPa). Heat is transferred through the walls of these tubes to the lower pressure secondary coolant located on the secondary side of the exchanger where the coolant evaporates to pressurized steam (saturated steam 280°C; 536°F; 6,5 MPa). The pressurized steam leaves the steam generator through a steam outlet and continues to the steam turbine. The transfer of heat is accomplished without mixing the two fluids to prevent the secondary coolant from becoming radioactive. The primary coolant leaves (water 295°C; 563°F; 16MPa) the steam generator through primary outlet and continues through a cold leg to a reactor coolant pump and then into the reactor.

We hope, this article, Boiling – Boiling Characteristics, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.