The Law of Conservation of Matter – Conservation of Mass

The law of conservation of matter or principle of matter conservation states that the mass of an object or collection of objects never changes over time, no matter how the constituent parts rearrange themselves.

The mass can neither be created nor destroyed.

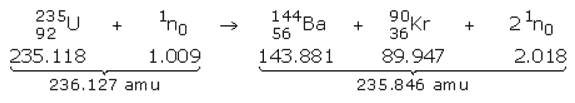

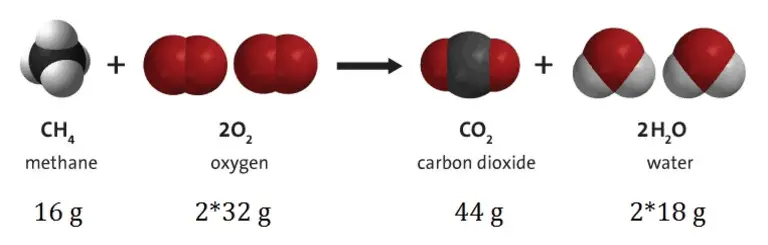

The law requires that during any nuclear reaction, radioactive decay or chemical reaction in an isolated system, the total mass of the reactants or starting materials must be equal to the mass of the products.

Historically, already the ancient Greeks proposed the idea that the total amount of matter in the universe is constant. The principle of conservation of mass was first outlined by Mikhail Lomonosov in 1748. However, the law of conservation of matter (or the principle of mass/matter conservation) as a fundamental principle of physics was discovered in by Antoine Lavoisier in the late 18th century. It was of great importance in progressing from alchemy to modern chemistry. Before this discovery, there were questions like:

- Why a piece of wood weighs less after burning?

- Can a matter or some of its part disappear?

In the case of burned wood the problem was the measurement of the weight of released gases. Measurements of the weight of released gases was complicated, because of the buoyancy effect of the Earth’s atmosphere on the weight of gases. Once understood, the conservation of matter was of crucial importance in the progress from alchemy to the modern natural science of chemistry.

The Law of Conservation of Matter in Special Relativity Theory

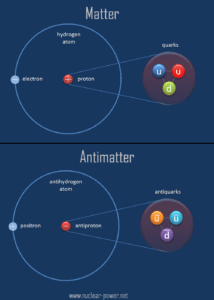

At the beginning of the 20th century, the notion of mass underwent a radical revision. Mass lost its absoluteness. One of the striking results of Einstein’s theory of relativity is that mass and energy are equivalent and convertible one into the other. Equivalence of the mass and energy is described by Einstein’s famous formula E = mc2. In words, energy equals mass multiplied by the speed of light squared. Because the speed of light is a very large number, the formula implies that any small amount of matter contains a very large amount of energy. The mass of an object was seen to be equivalent to energy, to be interconvertible with energy, and to increase significantly at exceedingly high speeds near that of light. The total energy of an object was understood to comprise its rest mass as well as its increase of mass caused by increase in kinetic energy.

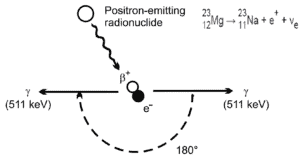

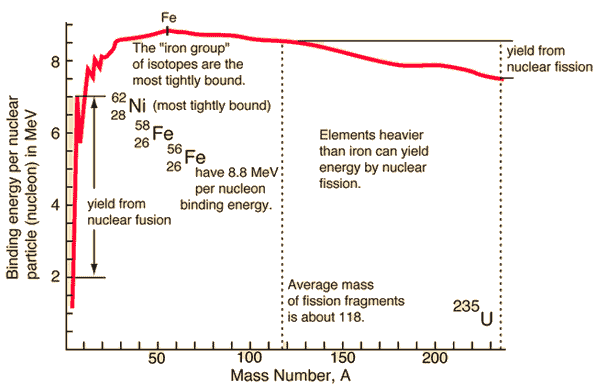

In special theory of relativity certain types of matter may be created or destroyed, but in all of these processes, the mass and energy associated with such matter remains unchanged in quantity. It was found the rest mass an atomic nucleus is measurably smaller than the sum of the rest masses of its constituent protons, neutrons and electrons. Mass was no longer considered unchangeable in the closed system. The difference is a measure of the nuclear binding energy which holds the nucleus together. According to the Einstein relationship (E = mc2) this binding energy is proportional to this mass difference and it is known as the mass defect.

Source: hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu

During the nuclear splitting or nuclear fusion, some of the mass of the nucleus gets converted into huge amounts of energy and thus this mass is removed from the total mass of the original particles, and the mass is missing in the resulting nucleus. The nuclear binding energies are enormous, they are of the order of a million times greater than the electron binding energies of atoms.

Generally, in both chemical and nuclear reactions, some conversion between rest mass and energy occurs, so that the products generally have smaller or greater mass than the reactants. Therefore the new conservation principle is the conservation of mass-energy.

See also: Energy Release from Fission

The Law of Conservation of Matter in Fluid Dynamics

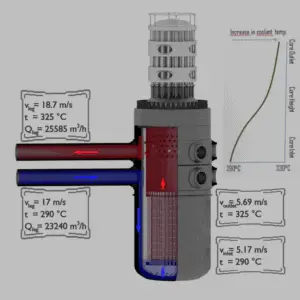

This principle is generally known as the conservation of matter principle and states that the mass of an object or collection of objects never changes over time, no matter how the constituent parts rearrange themselves. This principle can be use in the analysis of flowing fluids. Conservation of mass in fluid dynamics states that all mass flow rates into a control volume are equal to all mass flow rates out of the control volume plus the rate of change of mass within the control volume. This principle is expressed mathematically by following equation:

ṁin = ṁout +∆m⁄∆t

Mass entering per unit time = Mass leaving per unit time + Increase of mass in the control volume per unit time

This equation describes nonsteady-state flow. Nonsteady-state flow refers to the condition where the fluid properties at any single point in the system may change over time. Steady-state flow refers to the condition where the fluid properties (temperature, pressure, and velocity) at any single point in the system do not change over time. But one of the most significant properties that is constant in a steady-state flow system is the system mass flow rate. This means that there is no accumulation of mass within any component in the system.

See also: Continuity Equation

Continuity Equation

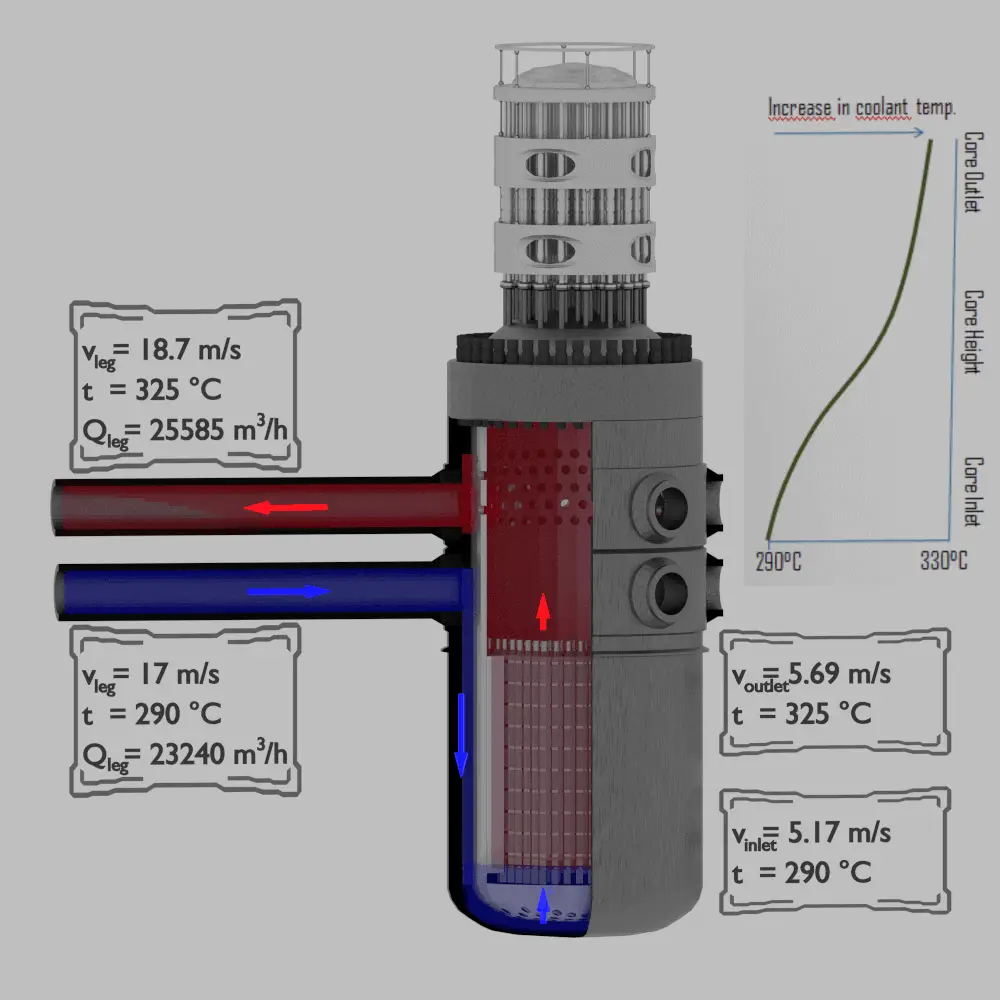

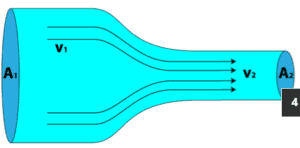

The continuity equation is simply a mathematical expression of the principle of conservation of mass. For a control volume that has a single inlet and a single outlet, the principle of conservation of mass states that, for steady-state flow, the mass flow rate into the volume must equal the mass flow rate out.

ṁin = ṁout

Mass entering per unit time = Mass leaving per unit time

This equation is called the continuity equation for steady one-dimensional flow. For a steady flow through a control volume with many inlets and outlets, the net mass flow must be zero, where inflows are negative and outflows are positive.

This principle can be applied to a streamtube such as that shown above. No fluid flows across the boundary made by the streamlines so mass only enters and leaves through the two ends of this streamtube section.

When a fluid is in motion, it must move in such a way that mass is conserved. To see how mass conservation places restrictions on the velocity field, consider the steady flow of fluid through a duct (that is, the inlet and outlet flows do not vary with time).

Differential Form of Continuity Equation

A general continuity equation can also be written in a differential form:

∂⍴⁄∂t + ∇ . (⍴ ͞v) = σ

where

- ∇ . is divergence,

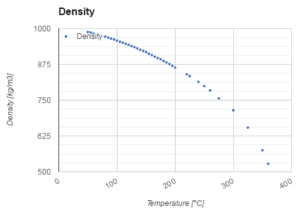

- ρ is the density of quantity q,

- ⍴ ͞v is the flux of quantity q,

- σ is the generation of q per unit volume per unit time. Terms that generate (σ > 0) or remove (σ < 0) q are referred to as a “sources” and “sinks” respectively. If q is a conserved quantity (such as energy), σ is equal to 0.

We hope, this article, Law of Conservation of Matter, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.