Thermal Efficiency of Rankine Cycle

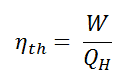

In general the thermal efficiency, ηth, of any heat engine is defined as the ratio of the work it does, W, to the heat input at the high temperature, QH.

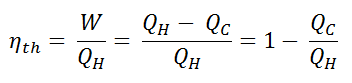

The thermal efficiency, ηth, represents the fraction of heat, QH, that is converted to work. Since energy is conserved according to the first law of thermodynamics and energy cannot be be converted to work completely, the heat input, QH, must equal the work done, W, plus the heat that must be dissipated as waste heat QC into the environment. Therefore we can rewrite the formula for thermal efficiency as:

This is very useful formula, but here we express the thermal efficiency using the first law in terms of enthalpy.

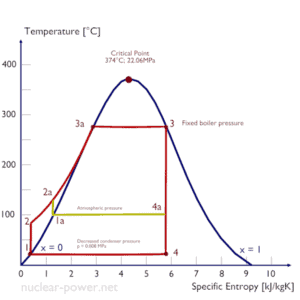

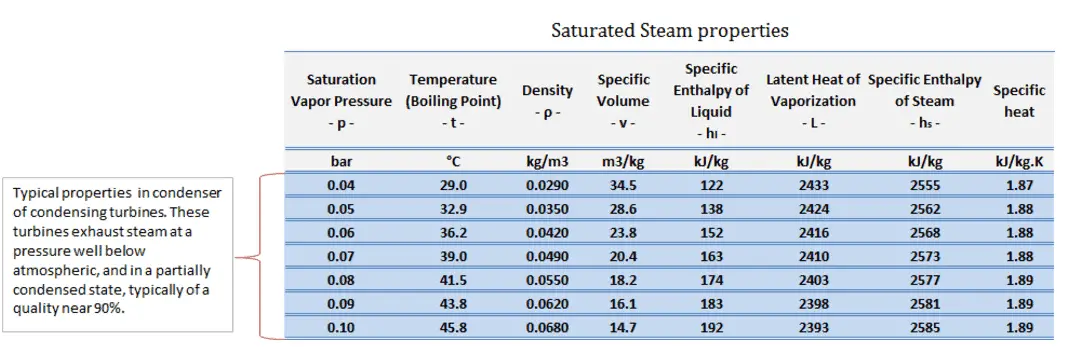

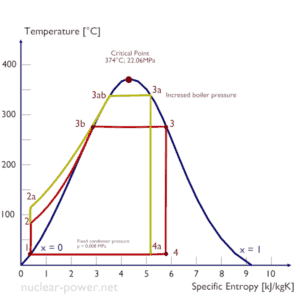

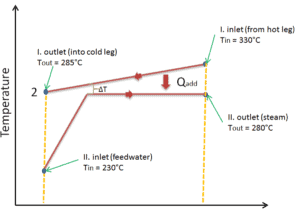

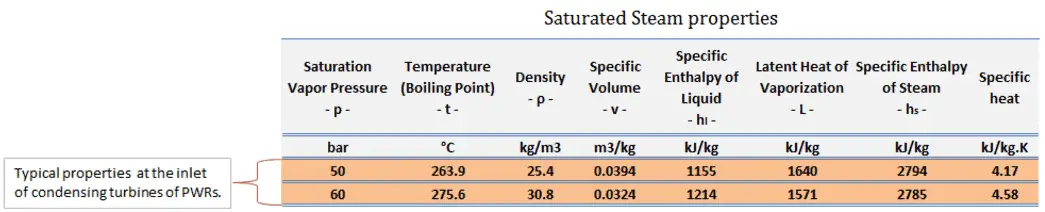

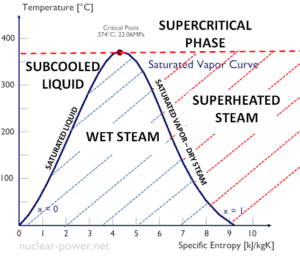

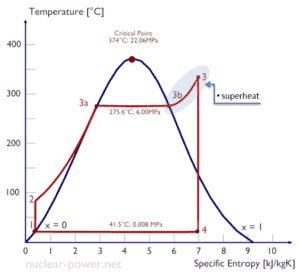

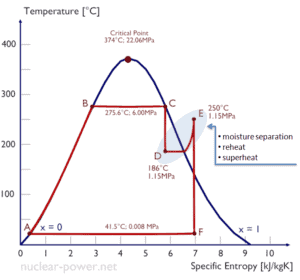

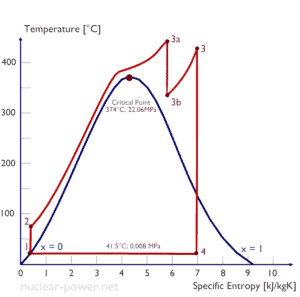

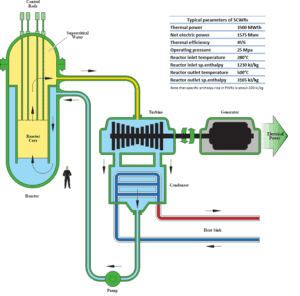

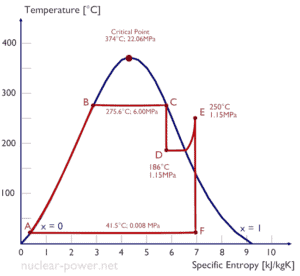

Typically most of nuclear power plants operates multi-stage condensing steam turbines. In these turbines the high-pressure stage receives steam (this steam is nearly saturated steam – x = 0.995 – point C at the figure; 6 MPa; 275.6°C) from a steam generator and exhaust it to moisture separator-reheater (point D). The steam must be reheated in order to avoid damages that could be caused to blades of steam turbine by low quality steam. The reheater heats the steam (point D) and then the steam is directed to the low-pressure stage of steam turbine, where expands (point E to F). The exhausted steam then condenses in the condenser and it is at a pressure well below atmospheric (absolute pressure of 0.008 MPa), and is in a partially condensed state (point F), typically of a quality near 90%.

In this case, steam generators, steam turbine, condensers and feedwater pumps constitute a heat engine, that is subject to the efficiency limitations imposed by the second law of thermodynamics. In ideal case (no friction, reversible processes, perfect design), this heat engine would have a Carnot efficiency of

= 1 – Tcold/Thot = 1 – 315/549 = 42.6%

where the temperature of the hot reservoir is 275.6°C (548.7K), the temperature of the cold reservoir is 41.5°C (314.7K). But the nuclear power plant is the real heat engine, in which thermodynamic processes are somehow irreversible. They are not done infinitely slowly. In real devices (such as turbines, pumps, and compressors) a mechanical friction and heat losses cause further efficiency losses.

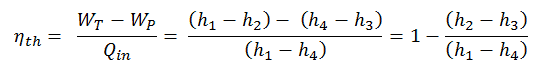

To calculate the thermal efficiency of the simplest Rankine cycle (without reheating) engineers use the first law of thermodynamics in terms of enthalpy rather than in terms of internal energy.

The first law in terms of enthalpy is:

dH = dQ + Vdp

In this equation the term Vdp is a flow process work. This work, Vdp, is used for open flow systems like a turbine or a pump in which there is a “dp”, i.e. change in pressure. There are no changes in control volume. As can be seen, this form of the law simplifies the description of energy transfer. At constant pressure, the enthalpy change equals the energy transferred from the environment through heating:

Isobaric process (Vdp = 0):

dH = dQ → Q = H2 – H1

At constant entropy, i.e. in isentropic process, the enthalpy change equals the flow process work done on or by the system:

Isentropic process (dQ = 0):

dH = Vdp → W = H2 – H1

It is obvious, it will be very useful in analysis of both thermodynamic cycles used in power engineering, i.e. in Brayton cycle and Rankine cycle.

The enthalpy can be made into an intensive, or specific, variable by dividing by the mass. Engineers use the specific enthalpy in thermodynamic analysis more than the enthalpy itself. It is tabulated in the steam tables along with specific volume and specific internal energy. The thermal efficiency of such simple Rankine cycle and in terms of specific enthalpies would be:

It is very simple equation and for determination of the thermal efficiency you can use data from steam tables.

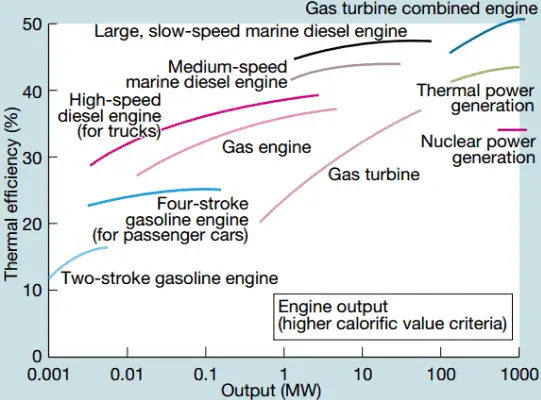

In modern nuclear power plants the overall thermal efficiency is about one-third (33%), so 3000 MWth of thermal power from the fission reaction is needed to generate 1000 MWe of electrical power. The reason lies in relatively low steam temperature (6 MPa; 275.6°C). Higher efficiencies can be attained by increasing the temperature of the steam. But this requires an increase in pressures inside boilers or steam generators. However, metallurgical considerations place an upper limits on such pressures. In comparison to other energy sources the thermal efficiency of 33% is not much. But it must be noted that nuclear power plants are much more complex than fossil fuel power plants and it is much easier to burn fossil fuel ,than to generate energy from nuclear fuel. Sub-critical fossil fuel power plants, that are operated under critical pressure (i.e. lower than 22.1 MPa), can achieve 36–40% efficiency.

Causes of Inefficiency

As was discussed, an efficiency can range between 0 and 1. Each heat engine is somehow inefficient. This inefficiency can be attributed to three causes.

- Irreversibility of Processes. There is an overall theoretical upper limit to the efficiency of conversion of heat to work in any heat engine. This upper limit is called the Carnot efficiency. According to the Carnot principle, no engine can be more efficient than a reversible engine (a Carnot heat engine) operating between the same high temperature and low temperature reservoirs. For example, when the hot reservoir have Thot of 400°C (673K) and Tcold of about 20°C (293K), the maximum (ideal) efficiency will be: = 1 – Tcold/Thot = 1 – 293/673 = 56%. But all real thermodynamic processes are somehow irreversible. They are not done infinitely slowly. Therefore, heat engines must have lower efficiencies than limits on their efficiency due to the inherent irreversibility of the heat engine cycle they use.

- Presence of Friction and Heat Losses. In real thermodynamic systems or in real heat engines, a part of the overall cycle inefficiency is due to the losses by the individual components. In real devices (such as turbines, pumps, and compressors) a mechanical friction, heat losses and losses in the combustion process cause further efficiency losses.

- Design Inefficiency. Finally, last and also important source of inefficiencies is from the compromises made by engineers when designing a heat engine (e.g. power plant). They must consider cost and other factors in the design and operation of the cycle. As an example consider a design of the condenser in the thermal power plants. Ideally the steam exhausted into the condenser would have no subcooling. But real condensers are designed to subcool the liquid by a few degrees of Celsius in order to avoid the suction cavitation in the condensate pumps. But, this subcooling increases the inefficiency of the cycle, because more energy is needed to reheat the water.

Thermal Efficiency Improvement – Rankine Cycle

There are several methods, how can be the thermal efficiency of the Rankine cycle improved. Assuming that the maximum temperature is limited by the pressure inside the reactor pressure vessel, these methods are:

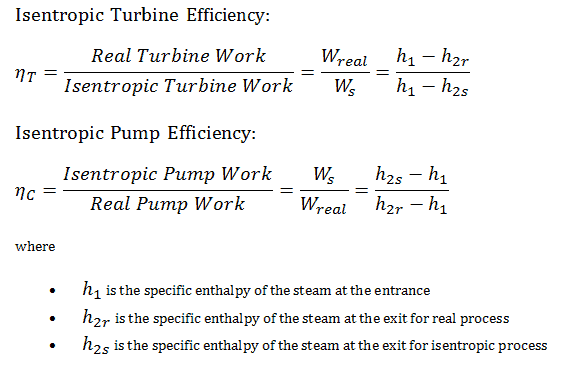

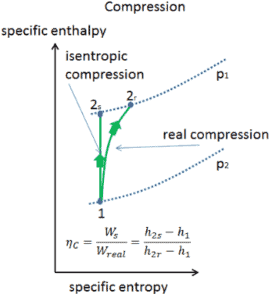

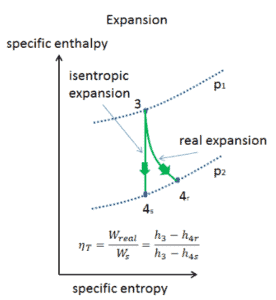

Isentropic Efficiency – Turbine, Pump

In previous chapters we assumed that the steam expansion is isentropic and therefore we used T4,is as the outlet temperature of the gas. These assumptions are only applicable with ideal cycles.

Most steady-flow devices (turbines, compressors, nozzles) operate under adiabatic conditions, but they are not truly isentropic but are rather idealized as isentropic for calculation purposes. We define parameters ηT, ηP, ηN, as a ratio of real work done by device to work by device when operated under isentropic conditions (in case of turbine). This ratio is known as the Isentropic Turbine/Pump/Nozzle Efficiency. These parameters describe how efficiently a turbine, compressor or nozzle approximates a corresponding isentropic device. This parameter reduces the overall efficiency and work output. For turbines, the value of ηT is typically 0.7 to 0.9 (70–90%).

See also: Isentropic Process

We hope, this article, Thermal Efficiency Improvement – Rankine Cycle, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.