Thermal Conduction – Heat Conduction

Thermal conduction, also called heat conduction, occurs within a body or between two bodies in contact without the involvement of mass flow and mixing. It is the direct microscopic exchange of kinetic energy of particles through the boundary between two systems. Heat transfer by conduction is dependent upon the driving “force” of temperature difference and the thermal conductivity (or the resistance to heat transfer). The thermal conductivity is dependent upon the nature and dimensions of the heat transfer medium. All heat transfer problems involve the temperature difference, the geometry, and the physical properties of the object being studied. In conduction heat transfer problems, the object being studied is usually a solid.

Thermal conduction, also called heat conduction, occurs within a body or between two bodies in contact without the involvement of mass flow and mixing. It is the direct microscopic exchange of kinetic energy of particles through the boundary between two systems. Heat transfer by conduction is dependent upon the driving “force” of temperature difference and the thermal conductivity (or the resistance to heat transfer). The thermal conductivity is dependent upon the nature and dimensions of the heat transfer medium. All heat transfer problems involve the temperature difference, the geometry, and the physical properties of the object being studied. In conduction heat transfer problems, the object being studied is usually a solid.

Microscopically this mode of energy transfer is attributed to free electron flow from higher to lower energy levels, lattice vibration and molecular collision. Consider a block of stone at high temperature, that consists of atoms that are oscillating intensely around their average positions. At low temperatures, the atoms continue to oscillate, but with less intensity.  If a hotter block of stone is put in contact with a cooler block, the intensely oscillating atoms at the edge of the hotter block gives off its kinetic energy to the less oscillating atoms at the edge of the cool block. In this case there is energy transfer between these two blocks and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler block by this random vibrations. The modern view is to ascribe the energy transfer to lattice waves induced by atomic motion. In an electrical insulators, the energy transfer is exclusively via these lattice waves. In a conductor, it is also due to the translational motion of the free electrons.

If a hotter block of stone is put in contact with a cooler block, the intensely oscillating atoms at the edge of the hotter block gives off its kinetic energy to the less oscillating atoms at the edge of the cool block. In this case there is energy transfer between these two blocks and heat flows from the hotter to the cooler block by this random vibrations. The modern view is to ascribe the energy transfer to lattice waves induced by atomic motion. In an electrical insulators, the energy transfer is exclusively via these lattice waves. In a conductor, it is also due to the translational motion of the free electrons.

See also: Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

In general, metals are usually good conductors of thermal energy. It is closely associated with its good electrical conductivity. For metals, the thermal conductivity is quite high, and those metals which are the best electrical conductors are also the best thermal conductors. This is due to the way that metals bond chemically. Metallic bonds have free-moving electrons (free electrons) that transfer thermal energy rapidly through the metal. The electron fluid of a conductive metallic solid conducts most of the heat flux through the solid. Phonon flux is still present, but carries less of the energy. These mechanisms of thermal conduction will be discussed later.

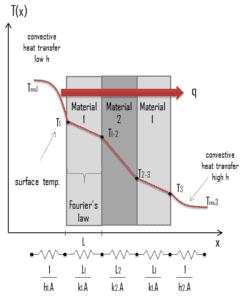

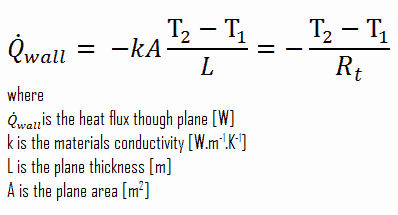

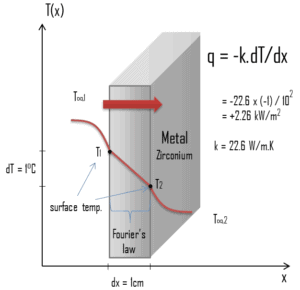

Fourier’s law of Thermal Conduction

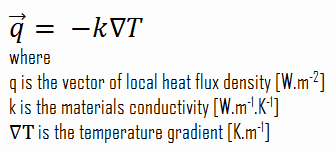

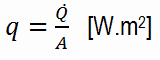

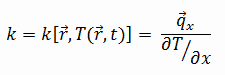

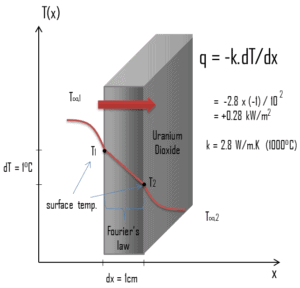

Heat transfer processes can be quantified in terms of appropriate rate equations. The rate equation in this heat transfer mode is based on Fourier’s law of thermal conduction. This law states that the time rate of heat transfer through a material is proportional to the negative gradient in the temperature and to the area, at right angles to that gradient, through which the heat flows. Its differential form is:

As can be seen, to solve the Fourier’s law we have to involve the temperature difference, the geometry, and the thermal conductivity of the object. This law was first formulated by Joseph Fourier in 1822 who concluded that “the heat flux resulting from thermal conduction is proportional to the magnitude of the temperature gradient and opposite to it in sign”.

Similarly as the Fourier’s law determines the heat flux through a slab, it can also be used to determine the temperature difference, when q is known. This can be used for calculation of the temperature in the centre of fuel pellet as will be shown in following sections.

Heat Conduction Equation

In previous sections, we have dealt especially with one-dimensional steady-state heat transfer, which can be characterized by the Fourier’s law of heat conduction. But its applicability is very limited. This law assumes steady-state heat transfer through a planar body (note that, Fourier’s law can be derived also for cylindrical and spherical coordinates), without heat sources. It is simply the rate equation in this heat transfer mode, where the temperature gradient is known.

In previous sections, we have dealt especially with one-dimensional steady-state heat transfer, which can be characterized by the Fourier’s law of heat conduction. But its applicability is very limited. This law assumes steady-state heat transfer through a planar body (note that, Fourier’s law can be derived also for cylindrical and spherical coordinates), without heat sources. It is simply the rate equation in this heat transfer mode, where the temperature gradient is known.

But a major problem in most conduction analyses is to determine the temperature field in a medium resulting from conditions imposed on its boundaries. In engineering, we have to solve heat transfer problems involving different geometries and different conditions such as a cylindrical nuclear fuel element, which involves internal heat source or the wall of a spherical containment. These problems are more complex than the planar analyses we did in previous sections. Therefore these problems will be the subject of this section, in which the heat conduction equation will be introduced and solved.

See also: Heat Equation

Heat Conduction Equation – General Form

The heat conduction equation is a partial differential equation that describes the distribution of heat (or the temperature field) in a given body over time. Detailed knowledge of the temperature field is very important in thermal conduction through materials. Once this temperature distribution is known, the conduction heat flux at any point in the material or on its surface may be computed from Fourier’s law.

The heat equation is derived from Fourier’s law and conservation of energy. The Fourier’s law states that the time rate of heat transfer through a material is proportional to the negative gradient in the temperature and to the area, at right angles to that gradient, through which the heat flows.

A change in internal energy per unit volume in the material, ΔQ, is proportional to the change in temperature, Δu. That is:

∆Q = ρ.cp.∆T

General Form

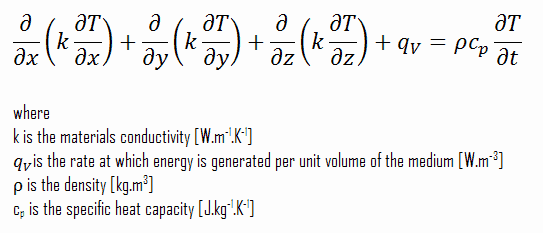

Using these two equation we can derive the general heat conduction equation:

This equation is also known as the Fourier-Biot equation, and provides the basic tool for heat conduction analysis. From its solution, we can obtain the temperature field as a function of time.

In words, the heat conduction equation states that:

At any point in the medium the net rate of energy transfer by conduction into a unit volume plus the volumetric rate of thermal energy generation must equal the rate of change of thermal energy stored within the volume.

See also: Thermal Diffusivity

Example – Thermal Conduction in Fuel Rod

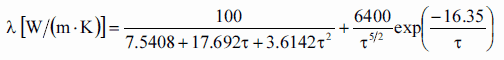

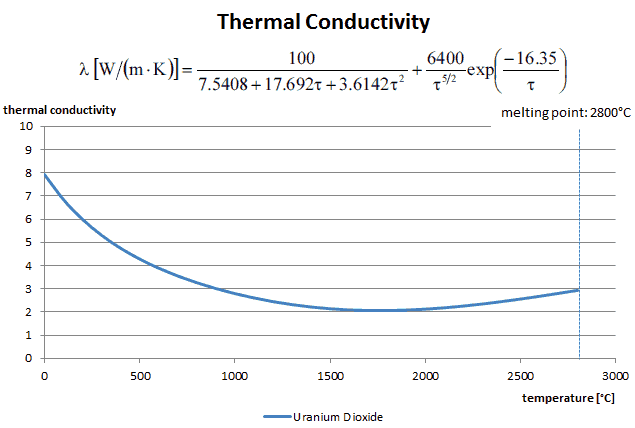

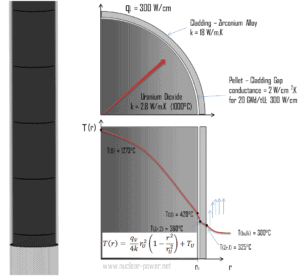

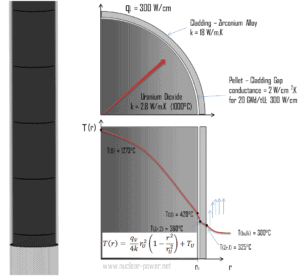

Most of PWRs use the uranium fuel, which is in the form of uranium dioxide. Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid with very low thermal conductivity. On the other hand the uranium dioxide has very high melting point and has well known behavior. The UO2 is pressed into cylindrical pellets, these pellets are then sintered into the solid.

Most of PWRs use the uranium fuel, which is in the form of uranium dioxide. Uranium dioxide is a black semiconducting solid with very low thermal conductivity. On the other hand the uranium dioxide has very high melting point and has well known behavior. The UO2 is pressed into cylindrical pellets, these pellets are then sintered into the solid.

These cylindrical pellets are then loaded and encapsulated within a fuel rod (or fuel pin), which is made of zirconium alloys due to its very low absorption cross-section (unlike the stainless steel). The surface of the tube, which covers the pellets, is called fuel cladding.

See also: Thermal Conduction of Uranium Dioxide

Thermal and mechanical behavior of fuel pellets and fuel rods constitute one of three key core design disciplines. Nuclear fuel is operated under very inhospitable conditions (thermal, radiation, mechanical) and must withstand more than normal conditions operation. For example temperatures in the centre of fuel pellets reach more than 1000°C (1832°F) accompanied by fission-gas releases. Therefore detailed knowledge of temperature distribution within a single fuel rod is essential for safe operation of nuclear fuel. In this section we will study heat conduction equation in cylindrical coordinates using Dirichlet boundary condition with given surface temperature (i.e. using Dirichlet boundary condition). Comprehensive analysis of fuel rod temperature profile will be studied in separate section.

Temperature in the centerline of a fuel pellet

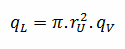

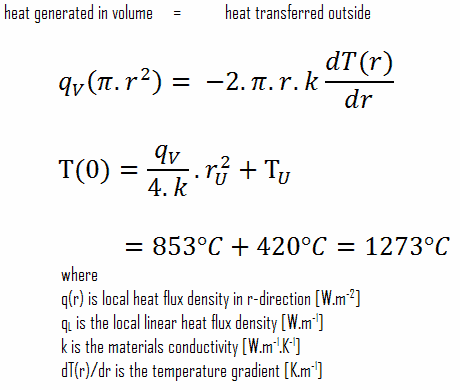

Consider the fuel pellet of radius rU = 0.40 cm, in which there is uniform and constant heat generation per unit volume, qV [W/m3]. Instead of volumetric heat rate qV [W/m3], engineers often use the linear heat rate, qL [W/m], which represents the heat rate of one meter of fuel rod. The linear heat rate can be calculated from the volumetric heat rate by:

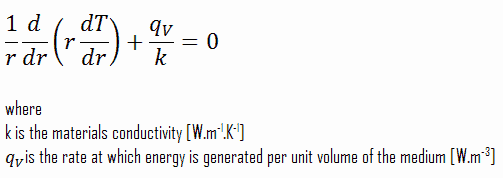

The centreline is taken as the origin for r-coordinate. Due to symmetry in z-direction and in azimuthal direction, we can separate of variables and simplify this problem to one-dimensional problem. Thus, we will solve for the temperature as function of radius, T(r), only. For constant thermal conductivity, k, the appropriate form of the cylindrical heat equation, is:

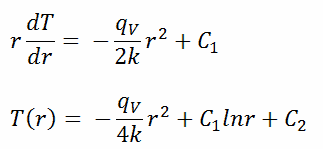

The general solution of this equation is:

where C1 and C2 are the constants of integration.

Calculate the temperature distribution, T(r), in this fuel pellet, if:

Calculate the temperature distribution, T(r), in this fuel pellet, if:

- the temperatures at the surface of the fuel pellet is TU = 420°C

- the fuel pellet radius rU = 4 mm.

- the averaged material’s conductivity is k = 2.8 W/m.K (corresponds to uranium dioxide at 1000°C)

- the linear heat rate is qL = 300 W/cm and thus the volumetric heat rate is qV = 597 x 106 W/m3

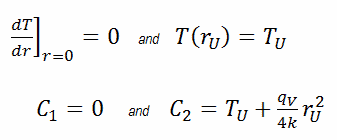

In this case, the surface is maintained at given temperatures TU. This corresponds to the Dirichlet boundary condition. Moreover, this problem is thermally symmetric and therefore we may use also thermal symmetry boundary condition. The constants may be evaluated using substitution into the general solution and are of the form:

The resulting temperature distribution and the centerline (r = 0) temperature (maximum) in this cylindrical fuel pellet at these specific boundary conditions will be:

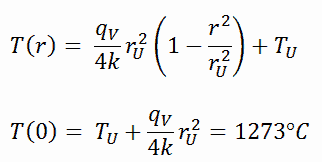

The radial heat flux at any radius, qr [W.m-1], in the cylinder may, of course, be determined by using the temperature distribution and with the Fourier’s law. Note that, with heat generation the heat flux is no longer independent of r.

∆T in fuel pellet

Detailed knowledge of geometry, outer radius of fuel pellet, volumetric heat rate, and the pellet surface temperature (TU) determines ∆T between outer surface and centerline of fuel pellet. Therefore we can calculate the centerline temperature (TZr,2) simply using the energy conservation between heat generated in the volume and the transferred outside the volume:

The following figure shows the temperature distribution in the fuel pellet at various power levels.

______

The temperature in an operating reactor varies from point to point within the system. As a consequence, there is always one fuel rod and one local volume, that are hotter than all the rest. In order to limit these hot places the peak power limits must be introduced. The peak power limits are associated with a boiling crisis and with the conditions which could cause fuel pellet melt. However, metallurgical considerations place an upper limits on the temperature of the fuel cladding and the fuel pellet. Above these temperatures there is a danger that the fuel may be damaged. One of the major objectives in the design of a nuclear reactors is to provide for the removal of the heat produced at the desired power level, while assuring that the maximum fuel temperature and the maximum cladding temperature are always below these predetermined values.

We hope, this article, Thermal Conduction – Heat Conduction, helps you. If so, give us a like in the sidebar. Main purpose of this website is to help the public to learn some interesting and important information about thermal engineering.